On October 23, 2021, subscribers to Opening a Bottle will have access to our Virtual Tasting Seminar on natural wines. It occurred to me while redesigning this website that (a) we often feature natural wines on this site, despite not dogmatically being a “natural wine website” and (b) the landscape of the natural wine scene is a very confusing and opaque. It seemed like as good a time as any to tackle the topic! However, given the vastness of “natural wine,” this program will be structured a little differently, as the tasting portion will be more social rather than an academic comparison. As usual, up to 8 non-subscribers can buy tickets through Eventbrite for $35/log-in.

Below you will find everything you need as a paying subscriber to access the event: a description of the class and how to briefly vet natural wines within a store or online shop so that you can stock up for the show. But first: your Zoom credentials to access the event.

Navigate This Study Guide

Zoom Credentials

To join the virtual tasting, use the following log-in credentials to Zoom. We will begin at 8pm EST/5pm PST (U.S.) sharp on October 23, 2021. I am looking forward to it.

Topic: What is Natural Wine and Should I Care?

Time: Oct 23, 2021 08:00 PM Eastern Time (US and Canada)

Join Zoom Meeting

Meeting ID: 857 8605 7627

Passcode: NattyWine

What is Natural Wine and Should I Care?

“Natural wine” is a nebulous term at best. To deem something “natural” does not require meeting any universally agreed upon threshold for any criteria. This opens the door to quite a bit of greenwashing (i.e. be leery of the phrase “clean wine.”)

However, natural wine has become an important movement for many reasons. For one, consumers worldwide are taking more of an interest in how products are made, how sustainable they are to the environment, and how they might effect their body once ingested.

But perhaps even more so, we are curious about why wines taste differently from one to the next. Sameness, even consistency, is out; terroir and variation are in. To reveal the unique attributes of a wine in the glass, it would stand to reason that a “less is more” approach in terms of winemaking would assist in the cause.

That is what natural winemaking strives for: the least amount of intervention in the process. That means no fertilizers, herbicides or pesticides in the vineyard; few if any chemical treatments; no cultured yeasts to initiate fermentation (versus ambient yeast already in the winery); and even minimal influence from the aging vessels, like oak. Perhaps most debated of all: that dose of sulfur that is used as a preservative. How much is too much and is it even necessary at all?

All of this ladders up to a clunkier, less sexy (but way more accurate) definition for this movement: low-intervention wines.

Truth be told, many of the world’s finest, most sought-after wines have some low-intervention aspect to them. That’s because many of the world’s finest wines are also adhering to a traditional way of making wine, which predates the advent of chemical agriculture in the mid-20th century.

Personally, I believe that many of the practices surrounding “natural wine” are vitally important to making a fine wine. However, there are also numerous examples of this “hands off” approach being a little too “hands off,” none more obvious and annoying to me than a heavy waft of a horse’s backside in the glass — the dreaded excess of brettanomyces.

My goal with this class is not to provide a foolproof method to navigating these waters. The cause and effect of winemaking is complicated, and wine labeling is still incredibly opaque. However, I do believe you’ll have a better understanding of this category overall, and will feel empowered to ask the right questions about the wines you shop for.

One last bit: there is a natural wine website out there called Not Drinking Poison. I am not that kind of guy. For one, all wine has alcohol, and you could make an argument that alcohol itself is a poison. But secondly, I won’t do any saber-rattling on the consumption of wines falling outside this category. You’ll probably even notice at certain points in the presentation that I have my own doubts about some of the principles found in natural wine. The tension between scientific evidence and sensory mystery is all part and parcel of being a wine lover.

So what will we cover in this class?

- What exactly is meant by “natural wine” and what the movement strives to achieve;

- How to decipher a wine’s “natural bona fides” and whether any of it matters to your palate;

- Differences between conventional, organic, biodynamic and sustainable winemaking techniques;

- Flaws that can arise from minimal-intervention wines;

- How to spot greenwashing in wine marketing (besides the obvious: a celebrity endorsement);

- Conundrums that face all winemakers in the age of climate change;

- And which regions (as well as some specific producers) are following through on their promise to make more terroir-driven wines via “natural” methods.

We will start promptly at 8pm Eastern (USA time).

Shopping for Natural Wines

At this time, we do not have a retail partner, but I am working on an arrangement with a very good natural wine shop based in Denver that is setting up an online retail space. If we can get this tied down by October 1, subscribers will be able to order specified wines directly from them. I likely will have no financial stake in this arrangement, but I do want to provide good service to all of you to make sourcing your wines as easy as possible for these events.

For this class, I would highly recommend having at least two open bottles that fit the criteria below. We will not be doing a comparative tasting, but rather I will present and pause a few times to answer questions, and — because we all love discussing what we’re drinking — open the floor to conversation on what’s working and what’s not working in the glass.

Why at least two wines? Well, I want to encourage you to climb out of your comfort zone a bit, but on the off-chance that you don’t like how one wine is tasting, you’ll have a fall-back bottle. Or better yet, invite a few friends over and make it three or four.

Here are some things to look for.

Organic Certification

Around the world, different third-party entities (often governmental) certify organic practices. This process is voluntary, and can be time-consuming and expensive, which means that not all organic wines are certified. To spot a certified wine, spin the bottle around and look at the back label for a certification logo. Two of the most common logos you will see are from the European Union or the USDA, and they look like this:

There is also a difference between “organic wine” and “made with organic grapes.” The latter means that some practice within the winery disqualifies them from being a fully organic product, but the grapes themselves come from organic vineyards.

Throughout this website, we call out practicing organic wines with a red leaf icon () and certified organic wines with a green leaf icon (). Learn more about why organic wine matters.

Biodynamic Certification

If you love wine, you cannot ignore biodynamics. Many of the world’s most iconic wineries have converted to this practice, and it’s not like they were struggling to sell wine before they made the switch. Oftentimes, they have gone biodynamic for quality and sustainability reasons.

Biodynamics seeks more holistic methods for vineyard management and winemaking practices. That means relying on certain compost concoctions and natural “teas” instead of chemicals, timing actions to the lunar cycles, and — by and large — treating the vineyard and the winery environment as part of a greater ecosystem.

Biodynamics has a few loony aspects that make it controversial. We’ll dive into all of this during the seminar.

As with organic wines, there is a difference between certified biodynamic (as noted by logos like the two that follow) and practicing biodynamic. More wineries fall into the latter camp, but cannot claim the name on their label. This is likely because they either didn’t want to be troubled with certification (i.e. the cost, the bureaucracy) or they disagree with certain aspects or practices within certification. There is a lot of picking and choosing among practicing biodynamic winemakers. I find that, for most consumers, splitting these hairs doesn’t matter.

Throughout this website, we call out practicing biodynamic wines with a red moon icon () and certified biodynamic wines with a green moon icon (). Learn more about why biodynamic wine matters.

Wine Regions with a High Percentage of Low-Intervention Winemakers

The following areas have an outsized reputation for low-intervention winemaking, largely because of their climate and culture.

- Beaujolais, France – Often considered the birthplace of the natural wine movement thanks to the Gang of Four winemakers — Thévenet, Lapierre, Foillard and Breton — who held firm to tradition during Bojo’s candy crush days of industrial nouveau. Now: a younger generation is taking over with incredible results.

- The Loire, France – Despite its tendency to wet conditions (which have often demanded assistance from chemicals to avoid rot), the Loire has a sterling reputation for organic and biodynamic viticulture, the latter being very popular here.

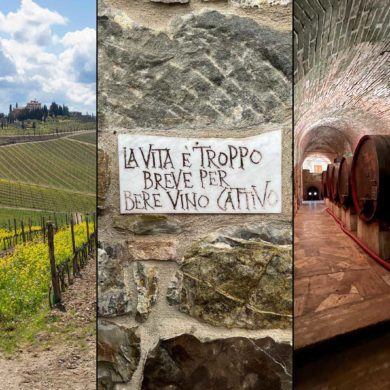

- Alsace, France (pictured at right) – Climate, climate, climate. In Alsace, going green in the vineyards is easy, and a culture of terroir-centric winemaking and multi-generational family businesses means that many — if not most — producers are natural in some way.

- Languedoc, France – Like Alsace, the Languedoc’s climate enables an easier transition to natural practices in the vineyard, but like an artist’s colony in a major city, the cheaper land and lighter adherence to strict appellation rules has attracted a fair share of natural renegades. That said, the Languedoc also produces a lot of co-op and bulk wine, so some research is required.

- Tuscany, Italy – Few would call Tuscany the epicenter of natural wine in Italy (just think of all the sameness traditionally associated with its wines), but in fact, the percentage of organic vineyards here is much higher than other regions of Italy, and a new ethos centered on wines of origin (rather than estate cachet) is helping turn things around.

- Sicily, Italy – In a way, Sicily is like France’s Languedoc: the climate is favorable, yes, but prices on land were suppressed for so long, it became appealing for “project” wines done by naturalistas. However, a commitment to the old ways of winemaking, thanks to the region’s astonishing history with the vine, has made it Italy’s go-to place for this category.

- Catalonia, Spain – Spain’s natural wine scene in general is very strong (again, thank you dry climate), and while Catalonia still has its fair share of industrial Cava and heavy-handed Priorat to avoid, it has a robust organic/biodynamic scene, especially for still wines in Penedès, Montsant and increasingly Priorat.

- Douro, Portugal – Long the bastion of Port, the Duoro is flipping the script with still red wines of increasing freshness and a turn toward more sustainable vineyard practices.

- California, Oregon and Washington – Our attention at Opening a Bottle has long been on European wines, so you will forgive us for lumping all of these together. But in truth, natural wine in America is less driven by regions, and more driven by individuals. Yes, certain pockets favor organic viticulture in the first place (like Washington State’s eastern reaches), and area’s long associated with spare-no-expense production to please market tastes (ahem, Napa) have made the pivot as well. But by and large, when crafting an overview, this is mostly by-producer terrain. So, which producers do I like who focus extensively on natural techniques?

- In California, look for: Lady of the Sunshine, Tablas Creek, Broc Cellars, Matthiasson, Arnot-Roberts and my personal favorite, Martha Stoumen.

- In Oregon, look for: Montinore, Maysara, Eyrie Vineyards, Troon Vineyards and my other personal favorite, Leah Jorgensen, who makes incredible red, rosé and yes, white wines from Cabernet Franc.

Importers That Specialize in Low-Intervention Wines

My favorite version of Spin the Bottle involves spinning the wine around to see who imports it. Importers often have their own aesthetic that they aspire toward, and that certainly follows suit with low-intervention wines. The following is by no means exhaustive, but it includes some of the bigger players as well as a couple of local importers/distributors to look for in the Rocky Mountain region (where I’m based, as well as many subscribers).

- Becky Wasserman & Co. – The recent passing of Becky Wasserman was a momentous occasion for the wine industry. Few people did more to educate Americans about Burgundy, the Loire and natural wine than her. The company carries her torch with a superb selection of wineries.

- Rosenthal Wine Merchant – An importer with an excellent “batting average” of quality. Their book of wines from Valle d’Aosta alone, while seemingly fringe, sums up their passion for traditional, natural wine.

- Kermit Lynch Wine Merchants – KLWM focuses on traditional wines, and in so many cases, that desire has lead to more natural practices. Bonus points: you can order their wines straight from their website.

- Louis/Dressner Selections – Among importers, they are an icon of the natural wine movement. Foradori, Occhipinti, and Radikon are among the superstars in their Italian portfolio.

- Polaner Selections – I know I keep saying “a great portfolio” this, a “great portfolio” that, but Polaner’s is truly crème de la crème.

- Oliver McCrum – An awesome book of Italian wines.

- Wilson Daniels – Hardly a “natty wine” focused importer, but their prestige clients have almost all universally converted to organic or biodynamic production. They’ve imported the world’s most famous winery, Domaine de la Romanée-Conti, for decades, and yes, DRC is biodynamic.

- Portovino Italiano – An array of largely natural Italian producers ranging from iconic and classic (e.g. Scarpa, Walter Massa, Luigi Tecce) to eclectic “porch-pounders” (e.g. Cardedu)

- deMaison Selections – When it comes to Spanish wines, deMaison rocks it with a stellar lineup of sustainably-minded producers. Bonus points for their ciders, too.

- Old World Wine Company – An impressive importer with a footprint in the Rocky Mountain region. A lot of overlap with Portovino, Selection Massale and Polaner Selections.

Honestly, you could scroll through Essential Winemakers of Italy and France lists and find plenty of them.

As always, if you are really struggling to find what you need, you can contact us with a question.