Situated in the northwestern corner of Italy, the province of Piedmont is heaven on earth for foodies. White truffles, hazelnuts, braised meats, silky yolk-rich pastas decked in sage butter …

And so much chocolate.

Best of all: the wines. For my money, no other wine region in Italy — perhaps in the world — offers more variety and quality. All of this has to do with two factors. The first is Piedmont’s geography and geology, which is a magical interaction of having the Alps on two sides, the Mediterranean Sea nearby, and rolling hills in the center with an interesting mix of clay, marl and sandy soils.

The second factor are the grapes. You may find Barbera, Arneis, Dolcetto and even Nebbiolo elsewhere in the world, but believe me … these wines are like short-term leases. Piedmont owns these grapes — especially its signature grape, Nebbiolo — and they thrive here in a way that cannot be duplicated.

To quickly come up to speed on the wines of Piedmont, host a wine-tasting party with any of the following wine flights.

The Classics

Who is for? The Newbie.

Number of wines: 5 // Ideal number of guests: 8 to 10

If you are unfamiliar with Piedmont’s wines, I would start here, with a flight that begins with a white, presents three degrees of red (each getting bolder and bigger as you go) and then a sweet sparkler to go with dessert.

Begin with Roero Arneis, a white wine with a nice dash of acidity that resembles apples, limes and nuts. It’s a peculiar white that doesn’t immediately resemble anything else, plus it has a fascinating backstory worth reading.

Next, segue to Dolcetto, the great table wine of Piedmont that is filled with interesting contradictions — light yet meaty, tannic yet refreshing. It goes great with pizza. While Dolcetto is high in tannin and low in acidity, the next wine — Barbera — is the opposite, and I find it to be one of the most versatile food-friendly red wines in the world. After Barbera, its time for Piedmont’s pinnacle wine, Nebbiolo. The most famous Nebbiolo come from the areas of Barolo and Barbaresco, and are labeled as such. They require ample aging (or several hours of decanting) but they project an unreal aroma that is beautiful and quite singular. You can save a little money and buy a Nebbiolo Langhe or Nebbiolo d’Alba, but it won’t be quite the same thing (although it is still a delicious wine). Finally, wrap up the evening with Moscato d’Asti, a fizzy, fun and sweet dessert wine.

Barbera d’Alba vs. Barbera d’Asti

Who is it for? Seekers of food-friendly reds

Number of wines: 2 // Ideal number of guests: 4

Nebbiolo may be the top wine in Piedmont, but many winemakers I have talked with have a special place in their heart for Barbera, and its two most common — and best — versions are an interesting study in contrasts.

Barbera d’Albahails from the steep and often fog-shrouded Langhe Hills residing to the south of the city of Alba. Barbera d’Asti comes from lower, sandier and drier hills residing to the south of the city of Asti. Because of these differences, Barbera d’Alba is more floral and delicate, while Barbera d’Asti is more concentrated and powerful, but see for yourself. If you have more people attending, do two wines from each region, but from different vintages.

Because of its acidity, Barbera ages very well. An old Barbera with 10-plus years of age can be a glorious thing.

All Nebbiolo

Who is for? Piedmont newcomers looking for the next step

Number of wines: 5 // Ideal number of guests: 12

Like Pinot Noir, Nebbiolo’s ability to absorb the attributes of its environment and convey them with complex aromas and flavors is legendary. It is among the world’s most expressive grapes, and fortunately, Piedmont’s Nebbiolos go beyond just expensive bottlings of Barolo and Barbaresco.

In this flight, gather an example of Nebbiolo Langhe (or Nebbiolo d’Alba), Roero Rosso, and Gattinara as well as Barbaresco and Barolo. Tasted side by side, you will see the many ways Nebbiolo conveys terroir in the glass. The first two wines do not have the stringent regulations and requirements as the last two, so they are often simpler and more accessible in youth. If the Gattinara, Barbaresco and Barolo are less than five years old, be sure to decant them for a few hours before serving, which will allow their tannins to soften and reveal more nuance. You’ll also note that with this flight I am recommending more guests to the party, meaning a smaller taste per person. This is by design: Nebbiolo is so tannic, it can leave your palate exhausted and incapable of making distinctions after several glasses, especially if you are drinking them without hearty foods.

Fun variation: There are some beautiful Nebbiolo wines made in the neighboring regions of Val d’Aosta and Lombardy. Lighter and almost reminiscent of Pinot Noir, these “mountain Nebbiolos” could be served first as an interesting counterpoint. Look for Valtellina Superiore or Arnad-Montjovet.

The Old School vs. New School

Who is it for? Wine enthusiasts of all stripes

Number of wines: 3 // Ideal number of guests: 8

For many years in Barolo and Barbaresco, there was a rift among winemakers about how to actually make their wine. On one side were the traditionalists, who favored a slower approach to macerating the Nebbiolo grapes (the better to extract all of its character, they argued) as well as aging them in large oak casks called botte. On the other side was a group of forward-thinking winemakers called the modernists, who favored shorter maceration times (it makes the wine more approachable at a younger age, they argued) and aging the wine in smaller oak barrique barrels.

The two schools remain, but you’d never know it looking at the label of the wines. Of all the bits of info they put on there, traditionalista and modernista is not one of them.

So why is it even important? Because these two schools make sizably different versions of a wine that is called the same thing.

For this wine flight, you’ll need to do a bit of research on a handful of winemakers, or you can find a copy of Matt Kramer’s Making Sense of Italian Wine, which does a great job of explaining who falls into which camp. (Even though the book is 10 years old, it still holds mostly true). Muddling matters a bit is the middle ground: winemakers who macerate for moderate amounts of time and use a mixture of oak vessels. So this flight includes all three, served on a continuum from “approachable” to “austere.”

If all this research is overwhelming, here are just the three wines you could buy for the tasting:

- Francesco Rinaldi “Brunate” Barolo (traditionalist)

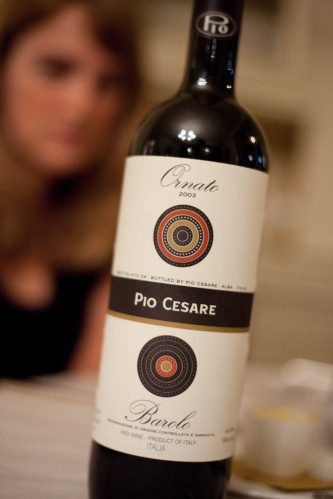

- Pio Cesare “Ornato” Barolo (middle-ground)

- Domenico Clerico “Pajanà” Barolo (modernist)

As with the Nebbiolo tasting, I recommend decanting these wines hours before the party if they are younger than 5 to 8 years from vintage. And be sure to buy wines from the same vintage if you can; these wines convey the weather of each year quite drastically.

A Taste of the Cru

Who is it for? Romantics and serious oenophiles

Number of wines: 3 to 4 // Number of guests: 8

The further we go on the list, the more advanced the subtleties become (and, unfortunately, the pricier the party gets). But if you are really into Piedmont wines after the first few tastings, you might someday find yourself holding a wine tasting of the various cru of Barolo and Barbaresco.

The word “cru” comes from France, and it simply refers to a specific vineyard that has consistently demonstrated its own personality. In Burgundy, Grand Cru vineyards (the highest order) are akin to sacred ground. The grapes they yield make a wine that is reportedly so exquisite, you’d gladly take out a second mortgage to drink them. (I wouldn’t know … I have only one mortgage and have yet to make friends with a Burgundy insider who would offer one to me).

Barolo and Barbaresco have more than 100 cru between them, but no formal stratification system on their degree of quality. Any ranking would be word of mouth and subject to personal tastes, and that’s the fun part: The object of this tasting is less about drawing distinctions, and more about encountering the various personalities of these vineyards.

There is Brunate, a Barolo cru of high regard that faces the south and is crowned by a riotously colored chapel. There is Ravera, in the town of Novello, which harbors a unique soil that is so rich in iron it creates a monster of a wine. Barolo’s Cannubi is considered the most historic of the area’s vineyards — somewhat of a birthplace for the modern-day wine (even though it has changed significantly since the mid 1700s). Barbaresco’s Martinenga vineyard one-ups Cannubi for historic longevity, dating back to Roman times (there is believed to have been a temple devoted to the god of Mars on the site).

No where else in Italy will you find such a densely packed area of named vineyards, each yielding single-source wines of unique character and compelling stories.

We recently hosted a Piedmont wine-tasting to introduce this region’s wines to our friends. I’ll post the tasting report in the next few days, so stay tuned.