What lies beneath the hand-laid stones of Volpaia says as much about Chianti Classico’s identity as the black rooster emblem, the galestro soil, and even the king grape of the region, Sangiovese.

It is stainless-steel pipes, running in a network of chases connecting seven separate, perfectly preserved buildings and therefore, the various winemaking operations of Castello di Volpaia. I would have never seen the pipes had Federica Mascheroni Stianti — whose grandparents purchased much of the village in 1966 — not removed a wooden panel to reveal one of their key junction points.

On the surface, Volpaia looks and feels like a medieval idyll and nothing more. “My family put all the wires underground, too.” Federica pointed out. “I think you see more wires from one building to the next in San Francisco than in Volpaia.”

Through these pipes, newborn Chianti Classico wine flows via gravity from the relatively tiny fermentation facility (also cloaked in a historic village building) to the barrel room for aging. This latter structure lies in the shadow of the Commenda di Sant’Eufrosino, a deconsecrated church built to impress the Knights of Malta in 1443. Federica explained that when her family purchased Volpaia in 1966, the church had been used for vehicle storage. “Can you believe they parked trucks in a church? Unbelievable!”

As surprising as these inner workings are, on the surface, Volpaia simply looks and feels like a medieval idyll that time skipped over. Forest and mountains and the numerous songs of birds surround it. Vineyards are judiciously placed on the surrounding slopes to the south (you might not even notice them on the approach), as are olive groves. These are all hallmarks of the Chianti Classico landscape, where efficiency and biodiversity are a multi-generational aspect of stewardship. Everything feels cared for.

And that’s what brings us back to those stainless-steel pipes. To convert the fortified village into a quality-minded winery, the Mascheroni Stianti family opted to use the existing structures for the various stages of winemaking, and connect them underground so that the wine could gently move through its various stages of élevage with minimal pumping.

But to do that, they had to “conserve the image of the village as it was in the past,” as Federica put it. Yes, the family’s love for Volpaia was strong, as was their commitment to preserve it, but the local authorities also wouldn’t allow it any other way.

“Do you see any wires?” Federica asked me. “Okay, this is another crazy part. My family put all the wires underground, too. I think you see more wires from one building to the next in San Francisco than in Volpaia.”

Explore This & Other Stories

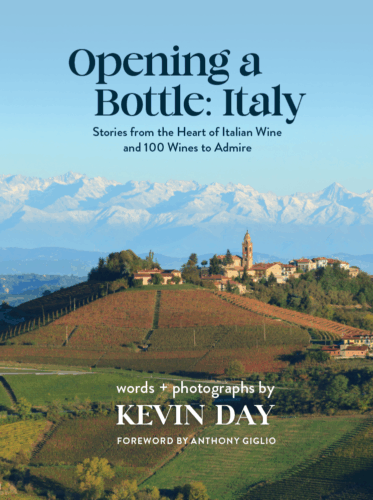

Ronchi di Cialla’s story is profiled in my new book, Opening a Bottle: Italy, which is now available in hardcover from BookBaby and via E-book on openingabottle.com.

Ronchi di Cialla’s story is profiled in my new book, Opening a Bottle: Italy, which is now available in hardcover from BookBaby and via E-book on openingabottle.com.

The book includes several new stories and 100 Wines to Admire from across Italy. Get your copy today!