If you taste the red wines of Tenuta di Capezzana, you are likely to be struck by their modern appeal: richness, spice, length, structure … It is all there.

Each kilometer up the road feels like a step back in time: stone walls, wild gardens, brick driveways where grass has replaced mortar, stout olive trees showing their ancient age.

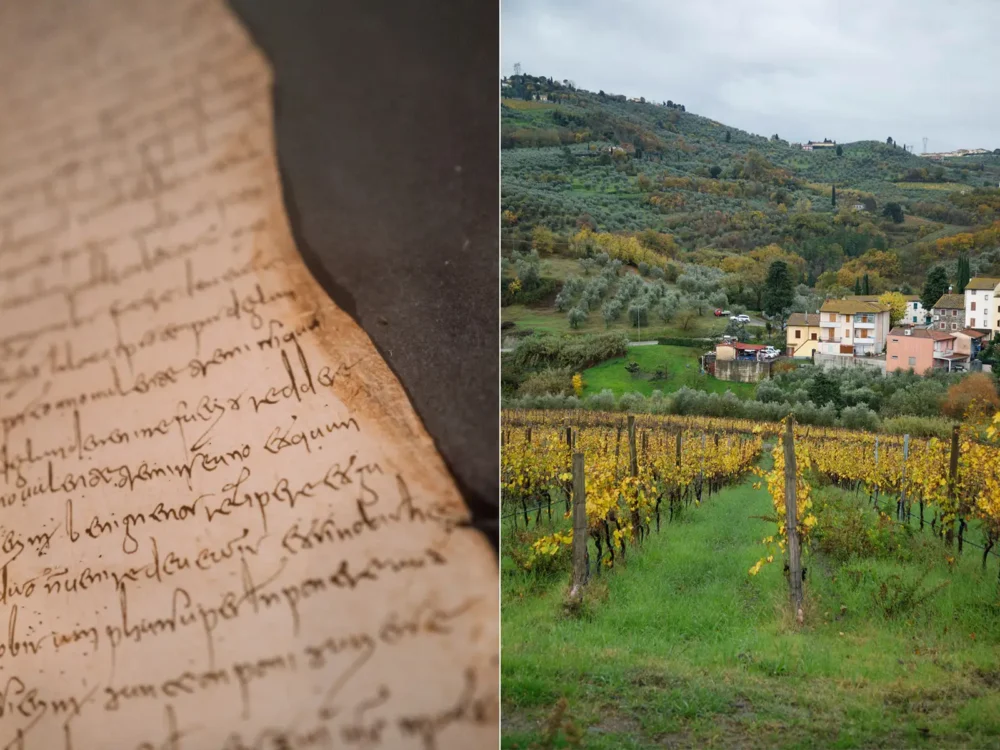

But when you travel up the road to this esteemed estate in the Carmignano hills west of Florence, each kilometer feels like a step back in time: stone walls, wild gardens, brick driveways where grass has replaced mortar, stout olive trees showing their ancient age. Catch this sight in mid-November light as I did — with golden leaves reigning down as a storm approached — and the timeless mood is only enhanced.

The journey culminates at a grand house and farm that is comfortably rooted in another era. There is no modern tasting room, no uniformed hosts in Polo shirts. Instead, footsteps echo, doors creak a little. Yet nothing seems to be decaying. The structure seems held together by its very soul.

Once you encounter Tenuta di Capezzana, it becomes impossible to apply modern expectations on the wines. They too, feel liberated from the present.

It All Started in 804

From a gravel courtyard, I stepped out of the sudden deluge into a dark foyer above Tenuta di Capezzana’s cellar. With me were Beatrice and Benedetta Contini Bonacossi, two sisters who preside over the once noble family’s legacy at the estate.

In modern Italy, nobility is purely historical and therefore, rather informal. In 1948, the ratified Italian constitution ended legal recognition of noble titles, though families could retain them in social and cultural contexts. More importantly, they could hold on to their estates.

This cultural capital often manifests in wine, where noble landholdings historically included vineyards. The Contini Bonacossi family of Tenuta di Capezzana are a prime example: proud of their land, heritage and stories, yet keenly aware that they are, at the end of the day, like any other winery that has to earn its customers.

To that end, they craft quintessential Carmignano reds, a brilliant rosato, two quenching white wines, a decadent vin santo, and a spicy, silky extra-virgin olive oil.They also welcome guests with an enoteca-osteria and a small inn. They are in the business of welcoming people to the traditions they uphold.

Last year marked the 100th anniversary of the Contini Bonacossi family’s stewardship over Capezzana. But this is an old-school estate that goes much further back, as a a framed document in the dimly lit passageway indicated.

“My sister Sandra found this parchment in the drawer where she worked in Florence,” Beatrice said. “It’s a document from 804 AD, which describes Capezzana for the first time.” She pointed at the word, barely recognizable amidst the beautiful, hard-written Latin that looked like hieroglyphics to me.

“It was the same kind of farm as today, with wine and olive oil production.”

She said the parchment was a contract stipulating the land’s boundaries, its yields and its worth — three coins, known in medieval Florence as dranice or denari.

“This was 1984, when she found the document. We couldn’t believe what she found.”

A Little Place Called Carmignano

To the northwest of Florence lies the Ombrone Pistoiese valley and the overlooked gem of a city, Pistoia. Draping the northeast-facing mountains to the south is the Carmignano DOCG, a tiny appellation with only a handful of producers. However, these hills have been producing notable wine for centuries, a fact underscored by Carmignano’s inclusion in a 1716 edict issued by Cosimo de Medici III which outline and protected the grand duchy’s four areas for superior wine production.

For roughly 500 years, this has been Cabernet country. Yes, Cabernet (and Cabernet Franc to be more specific). Long before Sassicaia and Tignanello imparted a spicy kiss on the world’s wine lovers, Carmignano was fostering this most French of grape varieties in the clefts of its hills. Caterina de Medici, who was Queen of France from 1547 to 1559, is often credited with its introduction.

Cabernet Franc took to the soil and climate beautifully, as did Cabernet Sauvignon, which eventually took precedence. While the stated rules for Carmignano wine require a minimum of 50% Sangiovese, the 10 to 20% that must be either of the two Cabernets, tends to make the boldest statement in the glass. Whether that taste profile registers as a wine of place, or something more international, is a line as fine as any in wine.

Tenuta di Capezzana is the largest producer in Carmignano, accounting for anywhere between 50% and 70% of the appellation’s wine each year. Even then, production is fairly small: less than half a million bottles. Like Chianti Rufina, this small zone is a tight community with a single large producer offering most of the world its first taste of the region.

Preserving Carmignano’s unique voice was not easy in the 19th and 20th century, as rural flight reduced the region to a Chianti footnote within the Montalbano subzone in the 1930s. This was followed by the ravages of World War II.

“Capezzana was occupied by the Germans toward the end of the war,” Beatrice told me as we entered the cavernous corridors of the underground cellar with her sister. According to Beatrice, the Nazis were canvasing Tuscany’s rural countryside and overtaking the nice estates to headquarter their field operations — and to pillage whatever supply they could. “Our great grandparents, they were quite clever to say, ‘Okay, let’s hide the wines.’ All of them were hidden in a farmer house cellar. So everything before the 1941 vintage was there.”

Because of this, the family was able to have an inventory to sell and get back into business immediately after the war. By the 1975, advocacy for Carmignano by Count Ugo Contini Bonacossi — Beatrice and Benedetta’s father — resulted in the region finally earning its own appellation recognition under Italian law. DOCG status came quickly, in 1990.

Last February at a special anniversary dinner hosted by Capezzana in Florence, I had the rare opportunity to taste one of the old wines that was saved from the war: the 1925 itself, the very first vintage. While much of its fruit and tension had subsided under a wave of tertiary tones, a spirited peppercorn character remained. One hundred years later, the pulse of Cabernet was still whispering.

To the Vineyards

As the rain subsided, one of the estate’s agronomists, Francesco Pasqua, drove me around to see Capezzana’s scattered vineyards. Mud was the order of the day, and temperatures felt cool but stable. Carmignano was saturated in emerald.

We visited Barbaroni where Sangiovese thrives, dove down a slippery track into Castagnati where a large retaining pond was swollen from recent rains, and ultimately climbed to the top of Trefiano, whose Sangiovese, Cabernet and Canaiolo create the potent Riserva wine of the same name.

Into the Vin Santaie

Returning to the estate, I was next shown the vin santaie, the special room where grapes are laid out on straw mats for a delicate aging process that yields one of the world’s most distinctive sweet wines: vin santo.

“You can see why our clone of Trebbiano is called Trebbiano Rosa,” Beatrice said, signaling the pink grapes lying upon and hanging from the racks. “We have used massal selection, so it is not a Trebbiano that you can buy from a nursery.” Because of its wilder character and richer skins, Trebbiano Rosa is more flavorful than Trebbiano Toscana. Lying on the mats was a small percentage of another native Tuscan grape, San Colombano.

Harvested in September, the grapes are air dried to concentrate sugars well into the winter. It used to be that they would dry all the way until March, but because winters have warmed so much, the process usually completes in January these days. The grapes are pressed, and the sticky sweet serum is fermented and stored in small chestnut casks called caratelli in a separate loft for seven years.

Unlike most modern wines, traditional vin santo is highly dependent on the fluctuates of room temperature. Benedetta regularly checks on the grapes, and has developed a feel for when she needs to open the windows to regulate the temperature and increase air flow.

“It is all by feel for her,” Beatrice said of her sister. “She comes seven days a week, two times a day just to check the humidity, to turn on the fans, to open or close the windows. She has said that this wine is like a fourth child.”

And the loft where the wines are aged in barrel adds complexity, the family feels, because of its astonishingly lack of temperature-control.

“Vin santo is like olive oil, in that it is not a product you make to make money,” Beatrice told me when I asked about the wine’s marketability in the modern age. “You make it because you are a Tuscan.”

If there is one international market that seems to understand vin santo’s appeal, it is the United Kingdom, she told me. Their affection for cheese at the end of a meal gives vin santo the proper platform to showcase its radiance and sweetness.

The Torch Passing

Benedetta’s son, Ettore Fantoni, joined us for the tasting and the lunch that followed. Ettore is absorbing as much of his mother’s winemaking acumen as he can, while being an eloquent spokesperson for the family’s approach to wine at the same time.

We tasted through a flight that included the estate’s delicate Chardonnay and the silky Trebbiano (from the Trebbiano Rosa clone, again). These two white wines have small production numbers, but they serve as quenching options on hot Tuscan days, making them an essential wine for summer visitors to the estate. The Barco Reale di Carmignano functions sort of as a baby Carmignano, while “Villa di Capezzana” and “Trefiano” offer endurance and structure for the years ahead.

Despite Carmignano’s storied Cabernet past, Ettore was quick to point out the vitality and importance of the most Tuscan of grapes, Sangiovese.

“Sangiovese gives us the long-term perspective in terms of aging. But also on the nose, it lends what we call sanguinella, the iron-type note, and — most typical of Carmignano — a sense of orange. That citric quality of Sangiovese really comes out in Carmignano.”

We concluded with a casual lunch in the enoteca, where the Tenuta di Capezzana’s silky and energetic extra virgin olive oil competed with the 2020 “Villa di Capezzana” Carmignano for the spotlight. I was satiated, content, and ready top stay another night. But duty in Chianti Classico called.

Ettore and Beatrice — dutiful, warm hosts that they are — surprised me by clearing the plates back to the kitchen. Perhaps the greatest nobility in Italy is being a gracious host.

Should You Go

Tenuta di Capezzana offers tours, an excellent enoteca and restaurant, and on-site accommodations. If you’re interested in visiting, I’m happy to help with arrangements and itinerary planning for Florence, Tuscany and beyond. Members of Opening a Bottle can earn a $100 credit toward travel planning services. Learn more below.