In the courtyard of the Vietti winery, my wife and I climbed into the back seat of a Land Rover. Luca Currado — the prominent and gregarious winemaker who has carried his family’s viticultural torch for the last three decades — climbed into the shotgun seat with a crate of wines between his feet. Elena, his wife, turned on the ignition, and away we went.

“This is a fun lunch,” Luca said. Vietti’s staff were celebrating the end of harvest by cooking up a massive meal, and we were going there instead of our original plan, which was to dine at a local restaurant. “All the vineyard workers, the winery workers, their wives — they like to prepare for everyone after the harvest, and they make food from their culture. They do it with heart, which is great.”

“Today we will be having Macedonian food,” Elena added, which led me to believe it was a multi-day cook-off.

“And it’s OK that we come?” I asked. It was probably the third time I had clarified this point, a symptom of my culture, in which preparing food for strangers is, sadly, considered a burden.

“Yes, yes, yes!” Luca answered enthusiastically. “I said there will be a famous American judge of food coming!” he added with a laugh. “When we eat as a team, we drink wines that other winemakers have brought when they visit,” he added. “We trade bottles. So let’s see what we have here.” Luca proceeded to lift bottles from the crate: a rosé from Domaine de Triennes, a couple of bottles of Croatian Zinfandel, two more rosé from Provence, a Grand Cuvée from Terlan, and a vintage Champagne which Luca called “Prosecco di Francese” with a sly smile.

Essential Piedmont Wines

I had made a point to visit Luca and Elena on this, our final full day in the Langhe Hills, because they had become my pen pals, in a way. Early supporters of my work, the two of them have helped me with a handful of articles, providing a winemaker’s insight where I would have only had personal assumptions.

And their wines … oh, their wines. Whether it was my first taste of their Roero Arneis, their Barbera d’Asti bottlings called “Tre Vigne” and “La Crena,” their Nebbiolo called “Perbacco,” or their Barolo classico called “Castiglione,” each had struck me as a singular expression of Piemontese wine at its best.

I had met Elena at a tasting in Denver, but this was my first time meeting Luca. Immediately, my wife and I were charmed by his persistently jovial mood. He made his first appearance after our tour had started with Elena, entering the main gate in the distance, a cell phone pressed against his ear. He looked up, flashed a million dollar smile, and waved as he walked into the far office door.

“He’s late,” Elena said, rolling her eyes knowingly. “When he’s late, its usually because he is talking to a journalist or a sommelier.”

The winery where most of Vietti’s wines are made is a stunning work of engineering. Burrowed into a hillside beneath the pretty village of Castiglione Falletto, it resembles a viticultural bunker, with several levels — a gravity-flow winery before that phrase ever became fashionable. It was built this way beginning in the 1600s, largely out of necessity given the area’s history of conflict. The rooms, tunnels and caverns create an enormous labyrinth filled with barrique barrels and oak casks. In one corner, Elena led us into a spooky tunnel where the walls seemed to be alive. Cob-webb laden bottles from the early 1900s lay in the alcoves.

The dichotomy from that dark tunnel to the bright and colorful vineyards outside the car’s window was striking. One of the first views on the drive was of the sloping Scarrone vineyard. Gold and green with fall color, Scarrone’s vines were already picked clean of grapes. Castiglione Falletto’s stout turret crowned the hill, Vietti at its feet. I tried to picture just how deep into the hillside the winery went as we sped along.

From Crazy Springs Creativity

When assessing the entirety of Luca Currado’s career, the Scarrone cru could be called the birthplace of Luca’s inventive streak. Or as he might call it, his first “crazy” idea (Luca and Elena love using this word, I noticed).

Scarrone is where Luca famously — and subversively — planted Barbera vines. It’s one of the best winemaking yarns I’ve heard (listen to it on this episode of I’ll Drink to That, it starts at the 1:14:00 mark). After proving himself as a capable winemaker with the family’s Barbera wines, his father, Alfredo, started to entrust Luca with their prized Nebbiolo. Luca’s first task was to replant the Nebbiolo in a Grand Cru Barolo vineyard.

Instead, Luca called the nursery and ordered Barbera vines — on purpose. It took almost two years for anyone to notice (the young vines look identical), but when they did, Luca’s father grew irate. He called the nursery to berate them, but the nursery had the fax confirmation to prove it was Luca’s doing.

“He had to show that he was mad at me,” Luca says in the podcast. “But I think in his heart he was happy … He understood that I did this for quality. Not for a stupid thing.”

The resulting Barbera from Scarrone quickly earned recognition as one of Piedmont’s best showings of the grape. And since then, no idea has been out of bounds for Luca.

He has tinkered with aging Barbera on the lees (that didn’t work), he has experimented with malolactic fermentation of Barolo in large casks, and in the late 1990s, he tried to tame the juice from a wild vineyard called Ravera with a lot of new oak. That also didn’t work. “Luca would say he was a little bit stupid with Ravera,” Elena told us. “He was young, he was experimenting,” she said casually, a suggestion that tinkering around and failing is the only way to move forward in wine.

The experiments with Ravera continued. In fact, Luca held the single-vineyard wine back from the market for 10 years until he was satisfied with its expression. Last year, the 2013 vintage scored a perfect 100 points from Antonio Galloni, making Vietti’s Ravera one of the most sought-after wines in Italy.

Inventiveness mixed with a healthy respect for tradition seems to be inherent in the Currado family blood. Alfredo is often credited with saving the Arneis grape from the dustbin of viticultural history in 1966 — an experiment fueled as much by curiosity as ambition. Today, Vietti’s Roero Arneis is truly one of Italy’s finest white wines, and 50 years later, Arneis is the go-to white wine grape all over Piedmont.

“He did 4,000 bottles that first vintage,” Luca told us. “Now, with the harvest in 2016, the region has produced 13 million bottles of Arneis.”

It is easy to call Alfredo’s Arneis experiment visionary, but Luca would rather call it a happy accident. “Every year we do an experiment. A majority go bad!”

Still, discovering an ancient grape hiding in plain sight is a tantalizing prospect, and as it turns out, the Langhe is full of such vines.

“I have a vineyard here down below with vines that are, I think, more than 100 years old, because they are pre-phylloxera. And they are very strange. We think they might be a form of pink Riesling.”

When I pressed Luca on whether he had made wine from these vines, he smiled and shook his head. “No, the grapes do not taste so good. I will keep it for the future generation.”

Nebbiolo in All Its Forms

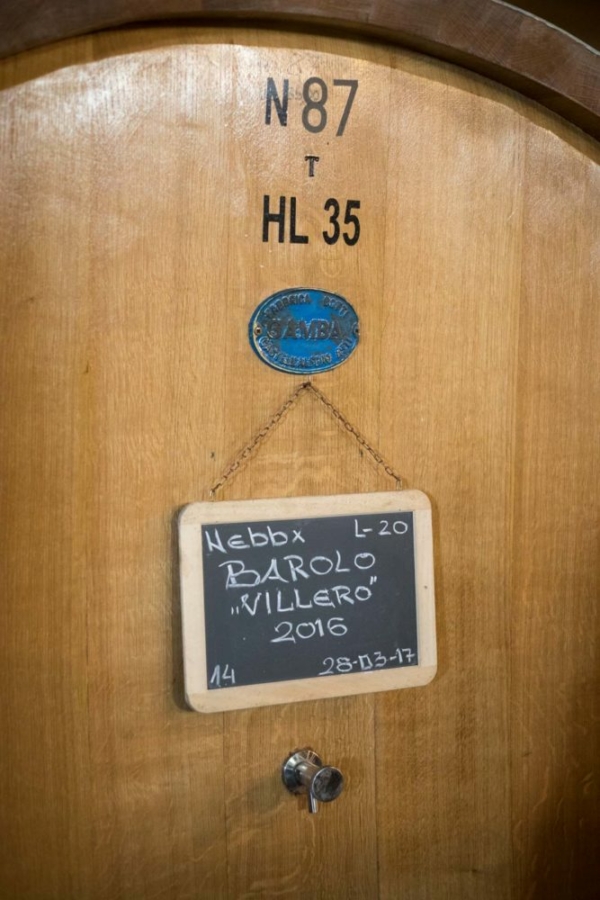

But the genius of Vietti is best shown in the winery’s work with Nebbiolo. The expressive, tannic, highly aromatic red grape variety is the solo actor in the wines of Barolo and Barbaresco, and Vietti was one of the first wineries in the 1960s to produce and promote single-vineyard versions to celebrate Nebbiolo’s nuances. Their bottlings from the Brunate, Ravera, Rocche di Castiglione and Lazzarito cru are highly detailed yet powerful wines; the kind of reds that will only reveal their true depths to those with years’ worth of patience.

Yet they still reveal plenty in their youth.

In the Vietti tasting room, we conducted a horizontal tasting of the 2013 Barolo Cru wines, and they confirmed some of the terroir principles of Barolo’s villages. That La Morra (in this case, the esteemed Brunate Cru) produces Barolo’s most delicate version. Novello — which has pole-vaulted in prestige in recent years, largely because of the Ravera Cru — has a tendency to express more depth of character. Serralunga d’Alba, in the extreme southeast corner of Barolo, yields the tour de force wines of the region. Vietti’s wine from the commune is called “Lazzarito” and it was like a drag racer: there was a lot of torque and gruff noise at first, but it quickly got off the line and sped forward in a beautiful direction.

As with my visit to Oddero the day before, Luca and Elena made it very clear that the “Barolo classico” — the wine blended from multiple Barolo vineyards — is every bit as important to their winery as the single-vineyard wines. Often selling for one third the price, the Barolo classico is a better value wine and more emblematic of the Barolo region as a whole, a philosophical point that has long created yet another divide among the area’s traditional winemakers. Giacomo Oddero, and perhaps more famously, Bartolo Mascarello, have long maintained that a blended Barolo is a true Barolo. But for Luca and Elena, the Barolo classico — simply called “Castiglione” — is more than just a holdover from the family’s traditional days.

“Crus are important,” Elena told me during the tour. “They are unique and collectible and expensive, and there is higher demand than there is availability. But after that? We have to sell.”

And sell they do. Vietti’s brand is among Barolo’s most recognizable around the world, in large part because of the accessibility of the Castiglione Barolo, as well as its little brother, a Langhe Nebbiolo called “Perbacco.”

Perbacco’s success is apparent to any casual observer: the wine is simply everywhere. I’ve seen it show up on wine lists countless times, ranging from an acclaimed sushi restaurant in San Francisco to the lone Italian wine at a modest cookhouse in rural Colorado. For many, Perbacco is their first taste of Nebbiolo.

But the conquest of Perbacco may have less to do with clever marketing, and more to do with clever subversion of the local wine regulations. That’s because it is an undercover Barolo.

“Perbacco could be labeled Barolo,” Elena told me. “Technically, it is one. By purpose, not by necessity.”

Whether it was initially seen as an experiment or just a “crazy idea,” Perbacco created a whole new market for Barolo winemakers. Because the Langhe Nebbiolo DOC designation has significantly looser requirements than Barolo DOCG (broader terrain to source grapes, less time aging in oak, etc.) the wines labeled as Langhe Nebbiolo have long been seen by winemakers and consumers as simpler and more affordable wines. But because of Vietti’s significant land holdings in 11 cru around the Barolo zone, they can create a widely distributed Barolo classico yet sell it for an entry-level price of around $20.

“When people say to me, ‘I got to know Vietti because of Perbacco,’ I am the most happy person,” Elena said. “Because the goal that we want is for people to be introduced to Vietti from the less expensive wines. Once they are confident and they trust the winery, they are much more happy to spend a bigger amount of money on the more expensive bottles of wine.”

Vietti’s Future

Barolo’s galaxy of winemakers can make your head spin. There are just so many to know. But what is remarkable when you tour the area’s wineries is the level of intimacy you get with the families producing these great wines. It’s what sets Barolo apart from Tuscany, Bordeaux and certainly Napa and Sonoma.

Perhaps that’s why the news was so shocking last year when Luca and Elena sold Vietti to an American businessman — one that made a fortune on convenient stores no less.

Barolo is changing. Rapidly. Land prices have soared through the roof, and tourism has significantly increased since the region earned an UNESCO World Heritage status in 2014. The sale of Vietti seemed to be another blow to the Old World charms of Barolo. Luca and Elena appeared to be cashing in, and one of the great family wineries seemed destined to become merely a brand.

Or did it? The news leaked prematurely, and Luca had to work his charms with the media so that everyone understood that he wasn’t going anywhere, and more importantly, that this influx of capital would allow Vietti to thrive for future generations. It was a tough sell, but anyone who has met him knows that Luca is an excellent salesman.

The facts on the ground are hard to appreciate from afar. According to Elena, the going price for one hectare of Barolo vineyard land is almost 3 million Euros. (“That’s crazy,” she exclaimed). It would be nice if Barolo could stay like it always has, but the global economy simply has other ideas. Chinese, Russian, American and Eastern European investors have been circling the area, keen to swoop up a finite commodity while the getting is good. It is not a climate that’s friendly to preserving a family’s holdings.

“The business was fantastic, but Barolo has suffered for its success,” Luca told Levi Dalton in a follow-up podcast. “Thirty percent of the vineyard we have, we rent … We rent the land for 20, 30 years, but when the piece of land comes back up for rent, the nephew or son would say ‘do you want to buy my land? I give you one day or I put (it) in auction.’ So you are obliged basically to buy back the land that you worked for all your life … You try with all your effort to buy, but you can do once, twice, but how many times do you have to have a gun to your head?”

According to Luca, this was an economic trend that meant one thing: without the financial capital to compete, the quality of Vietti’s wines would diminish with their key holdings, particularly the Castiglione Barolo and the Perbacco Nebbiolo, which rely on grapes from multiple plots of land.

And so the Currado family trait of pursuing “crazy ideas” reappeared. In 2014, they made an unsuccessful bid to buy Enrico Serafino in the neighboring Roero region. The winning bidder turned out to be the Krause family of Iowa, who had been quietly buying up vineyard land around Barolo. As soon as Kyle Krause approached Luca about working together, Luca saw it less as a hostile takeover, and more as an opportunity to further improve his wines.

“Here, everybody knows that if you have a good land — and you are not too stupid or arrogant — it is the only chance to make a great wine.”

Luca maintains that he still has “100% freedom” to do whatever he wants in the winery to make Vietti’s wines what they need to be. Perhaps the sale was a risky gambit, but as an outsider returning to the region for the first time in five years, I could see the radical influx of cash first hand. Barolo is changing: there are more restaurants, more wine bars catering to tourists, more swagger, in general. For God’s sakes, the iconic cedar tree of La Morra is now behind a gate to protect it — and the Barolo cru that surrounds it — from the hoards of tourists (we still managed to see a young couple try to sneak over the fence).

We can gasp all we want at Luca’s decision to sell, but I can’t help but see that the greater threat to his family winery was doing nothing and being squeezed out of Barolo’s best land.

A Family Lunch

When we arrived at the warehouse, lunch appeared to be set. Next to stacks upon stacks of crimson-colored harvest baskets, a series of long wooden tables stretched along the exterior wall. They were covered with plastic plates and utensils, wine glasses, wine bottles and loaves of crusty bread. Everyone had been waiting for us, but no one batted an eye at the strangers who accompanied Luca and Elena. (They knew: Luca likes talking to journalists).

We were introduced to team members from Italy, Macedonia, Germany and, yes, even America, and we were once again labeled “famous American food judges” by Luca as we took our seat at the far end of the table. Hailey and I were served first, and served generously. The food came constantly, a delicious parade of grape leaves stuffed with ground pork, tender stewed chicken with peppers and cabbage (one of the best dishes of the entire trip), and homemade casserole, all of it wiped clean from the plate with chunks of crusty bread.

It felt like the most natural of celebrations — breaking bread with friends and drinking “Prosecco di Francese,” Barbera d’Asti and Croatian Zinfandel. Most of the Italian conversation slipped through my grasp, but the jovial laughter, the animated stories, the smiles when we were served, it all left me deeply moved.

Luca and Elena could have taken us on a walk through the Scarrone cru or the nearby Lazzarito vineyard. They could have uncorked various vintages from the past. Instead, they brought us to the warehouse to celebrate a year’s worth of labor with their motley team of vineyard and winery workers. That alone, told me more about Vietti’s wine — and its future — than anything else could.