As my plane began its decent into San Luis Obispo’s airport last April, I found myself studying the landscape of the Edna Valley with a photographer’s reverence. There was just so much green: green mountains with dashes of orange poppy, green fields of grass, green orchard rows, and of course, green vineyards, which were already well ahead of schedule with their foliage.

Three days and several wine tastings later, I once again gazed through the oval window of my plane. But now I saw the landscape as something different: the valley was a conduit of cold air from the depths of Morro Bay to the north. The short arroyos on the west side were a side door for more oceanic influence — in this case, from San Luis Obispo Bay. And the series of sequential round-topped mounds known as the Nine Sisters? They were evidence of the Edna Valley’s volcanic past.

Having terroir rendered visible from the sky was a new experience.

The Edna Valley AVA is a cold place, despite its latitude. Located on California’s Central Coast about 90 miles north of Santa Barbara, the viticultural area has built its reputation on Chardonnay and Pinot Noir. Yet it was Albariño — the sea-loving varietal of Galicia, Monção and Melgaço — that left the biggest impression on me. Perhaps its the cool air and long growing season, or maybe its the mere presence of the ocean, but I had no idea this grape could be so thrilling.

Three days is a short time. I left with a lot of questions unanswered. But one question will take several vintages to answer: is California Albariño poised for a takeover, or will it merely thrill those of us on the fringe?

From Spain with Promise

While native to Spain and Portugal, Albariño’s origins are not fully known. It is possible that the monks of Cluny brought it to Spain in the 12th century when they traveled the Camino de Santiago. Because of this widely accepted theory, many have speculated that Albariño is a type of Riesling. But that possible relation is muddled by the fact that Riesling wasn’t documented until the 15th century. Either way, Albariño is a very ancient grape, with several centuries of adaptation to the northwestern Iberian Coast.

It is a grape of extremes: highly aromatic, very pale in color, very high in acidity. Its most recognizable trait is a salty sensation on the finish, but it is only noticeable when acidity and ripeness levels are kept in check in the vineyard. Albariño’s briny character makes it a gregarious party guest with seafood — the main reason it is called “vino del mar” by the Spanish.

Albariño is a bit of a homebody, but a few cuttings made their way to California in 1992, and they were planted in Santa Barbara County by vintner Brian Babcock. He wasn’t exactly thrilled with the results, but as the decade progressed — and winemakers sought out new varieties to satisfy shifting market demands — Albariño found a few collaborators, perhaps none more enthusiastic than the Edna Valley’s Niven family.

On a sunny afternoon this spring, John Niven introduced me to a handful of Albariño wines from the Edna Valley, alongside Mindy Oliver of Croma Vera Wines.

Across the street from us, Niven’s sprawling 900-acre Paragon Vineyard — the workhorse for his four wine brands Tangent, Baileyana, True Myth and Zocker — looked like a green ocean wave suspended in motion.

Most of Paragon is planted to Chardonnay, but Niven’s desire to find California’s next great white is evident in the vineyard’s minority plantings: Grüner Veltliner, Riesling, Grenache Blanc, Viognier and — most of all — 45 acres of Albariño.

“We feel like we have one of the greatest explorations of what cool-climate whites can do from a single site,” Niven says with an eager enthusiasm. Naturally, I want to counter it with some critical skepticism, but he is quickly proven correct: all of the aromatic white wines served that afternoon — from his precisely layered Grüner Zeltliner from Zocker (★★★★ 1/2) to the feral mysteries of a Pinot Gris from Stephen Ross (★★★★ 3/4) — had an indelible quality to them.

But standing out the most were the three Albariño in the tasting. Niven’s Tangent Stone Egg Albariño (★★★★ 3/4) has it both ways: it is complex yet refreshing. His winemaker, Rob Takigawa, has fermented this wine inside a concrete, egg-shaped vessel where the lees can spread out and affect more surface area. The resulting wine is layered heavily with tropical-fruit and yellow-flower aromas, with a pinpoint acidity that is light and sharp. The lees seem to round out the wine and soften the finish. It’s a crazy balancing act in a single sip.

Oliver’s Croma Vera Albariño (★★★★ 1/4) from the Spanish Springs Vineyard is somewhat smokey. Niners Estate’s version (★★★★) — from Jespersen Ranch — is somehow earthy.

For two days I had been tasting Pinot Noir and Chardonnay, but when this tasting was finished, I was convinced: they are on to something with Albariño in the Edna Valley.

Spain, Meet California. California, Meet Spain.

In 2008, after seven years of tinkering with Albariño, Niven decided to travel to Albariño’s spiritual homeland, Rías Baixas, on the northwest coast of Spain. There he discovered that, geographically speaking, Rías Baixas is the Central Coast’s Old World twin. In that uppermost corner of Spain, estuaries define the coastline, providing conduits of cool ocean air that move inland and caress the vines. This keeps the berries from getting burned in the summer.

The area receives significantly more rain than San Luis Obispo County, but what Niven saw and tasted surprised him. “California has had its challenges working with these esoteric varieties,” Niven says. “But we came back (from Spain) thinking ‘Ok, we’re a lot closer than we thought we were.’”

If the goal is emulation, that’s one thing. Putting a unique spin on Albariño is another matter. According to Niven, the differences between the Edna Valley’s current collection of Albariño and those of Rías Baixas are very slight. If anything, the only two advantages Rías Baixas has is a region-wide knowledge base, and ancient vine stock. “One-hundred-and-twenty-year-old vines will certainly give you different fruit,” he notes.

For Mindy Oliver — who was born and raised in Los Angeles — her journey toward starting a winery began with Spanish wines, all without visiting Spain. When she and her husband moved to San Luis Obispo to seek a quieter life, she began to drink Tempranillo and Albariño with increased interest, not because they were fashionable and available in a local wine shop, but because she tasted the local versions at the tasting rooms of Saucelito Canyon and Tangent Wines.

“I used to work in a cheese and wine shop throughout college,” she told me. “But it had always been in the back of my mind that I would come back to wine and do something with it.” Those Edna Valley wines from Spanish varieties were the epiphany she needed to start a winery.

On the palate, her Croma Vera Albariño (★★★★ 1/4) occupies the same mood you get from a crisp Sauvignon Blanc — only with a slight smokiness and a strong saline characteristic that screams for grilled fish or smoked oysters.

“When I started, my passion was these grapes,” she continued. “And they happen to grow really well on the Central Coast. I just thought, ‘all of these wineries around here are making excellent Pinots and excellent Chardonnay — we don’t need another winery to do that.'”

For now, production at Croma Vera is still small (around 800 cases per year), and that’s not unusual for this wine region on the rise. Several of the area’s rising stars are small, family-run operations with only a local following. Which begs yet another question: is Albariño just a local movement, or is it on the verge of becoming something larger?

Albariño’s Cali Grand Cru

To get to my accommodations in Pismo Beach each day, I drive by a rather unassuming vineyard off Price Canyon Road. This is the Spanish Springs Vineyard, which I am later told is the closest vineyard in California to the Pacific Ocean — although, I have heard that before up north in Fort Ross. Having visited both vineyards, this one does seem closer, perhaps because its lower elevation makes it feel as though you could hear the surf amongst the vines. Either way, what matters is how cold and foggy the site is. Grapes grown here regularly need the leaves pulled to allow as much sun in as possible, especially Albariño.

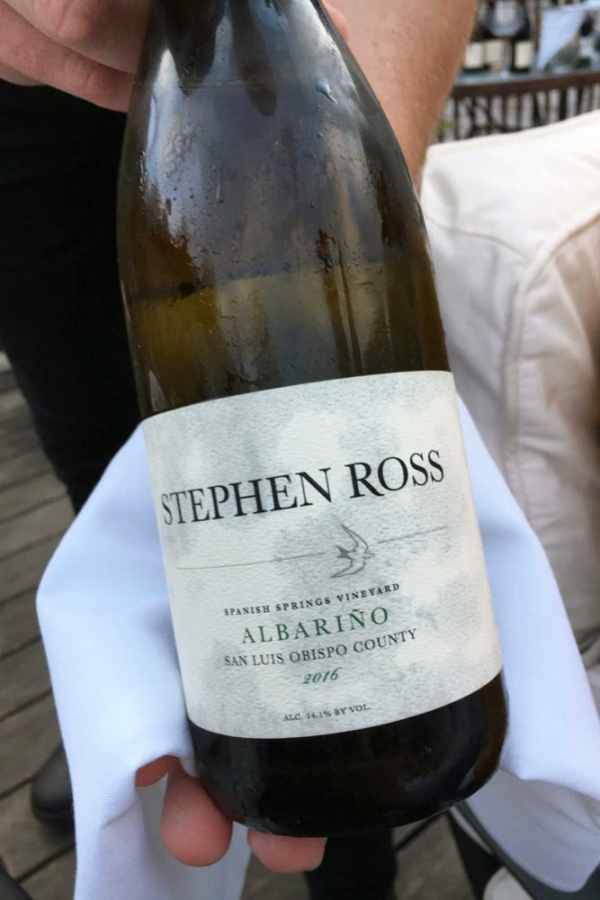

Mindy Oliver gets her Albariño grapes from Spanish Springs, as does Stephen Ross Dooley. Dooley is one of the most impressive winemakers I’ve come across in California. His modesty hides just how talented and sagely he is. Every detail in his Pinot Noir — as well as his delightfully complex Pinot Gris — is dialed in. In fact, the Stephen Ross Spanish Springs Vineyard Albariño (★★★★★) was easily the highest quality wine I tasted on the trip. Intensely aromatic and inviting throughout, it brought to mind crisp pear, bright lime, guava and lilies on the nose. It’s texture was thrilling, with a briny finish that provided momentum for the wine: a second sip, then a third, then a fourth. (Talk about a dangerous wine.)

For all the precision and care evident in this Albariño, Dooley seems pretty casual about it, as though the wine was a happy accident that resulted from poking around the Edna Valley. When I asked him why he started to make Albariño he noted it was a curiosity. “Well, I thought ‘it does well in Spain and Portugal. It should do well here,” he said.

He initially started with grapes from the Jespersen Vineyard, but eventually shifted in 2016 to Spanish Springs because the quality was so evident. And the market seems to be responding.

Earlier this year, Dooley and his team decided to double down on Albariño as the sole aromatic white of the future. “I think our Pinot Gris is awesome, but we may not continue that program,” he told me. The reason lies in the mercurial economics of producing familiar vs. esoteric grape varieties. “There is a reason I call it Pinot Gris and not Pinot Grigio,” he laughs.

Sauvignon Blanc — and particularly Pinot Gris/Pinot Grigio — can only fetch so much per bottle, no matter how special the terroir or how diligently they are made. With its curiosity factor still intact, California Albariño can get away with a higher price tag. If anything, the grape could be the next big thing on the Central Coast simply because its margins make the most sense.

I took this question back to John Niven, who certainly has the most skin the game: has Edna Valley Albariño arrived?

“It’s a tweener,” he responded. “If you look at the world of white wines, Chardonnay is top dog by far. But Albariño is jumping out of the pack. People’s palates are trending toward crisp, clean and light, and Albariño is all of those things.”

Note: This article was made possible by a media tour I joined, hosted by SLO Wine Country. Opening a Bottle retains sole editorial discretion for this article, as well as ownership of content assets. Learn more about my editorial policy.