Compelling Pinot Noir in the Americas tends to come from the fringes: vineyards situated where the climate gives just barely enough sunlight and warmth to sustain, foster and ripen the berries into something beautiful.

On our final day in wine country, Copain’s Wendling Vineyard Pinot Noir confirmed this “fringe theory” in the morning, and Fort Ross Winery’s Stagecoach Road Pinot Noir would demonstrate it in the afternoon.

After driving along the weaving and winding Russian River, we finally reached the Sonoma Coast, a fog-shrouded landscape that looks more like something J.R.R. Tolkein came up with than anything a tourism bureau would conceive. Broken and surf-pounded rocks, cliffs that demand distance, beaten-down vegetation … and not a sunbeam in sight.

Heading north on California Highway 1, we hair-pinned our way out of the fog, before turning right onto Meyers Grade Road. Soon, it felt as though we were flying: below us to the left, a perfectly soft, downy blanket of fog stretched completely to the horizon, covering the sea. It was a view I’d only seen before through the porthole window of an airliner.

For the next two miles, sporadic forest and pastureland punctuated that view of the fog. We soon came upon the Fort Ross Vineyard & Winery gate, and drove through a small, isolated vineyard — the closest one to the Pacific Ocean in California.

Beyond the vineyard, the road bent back into a mixed woodland where we encountered a doe and a fawn. Shortly after that, the tasting room appeared.

We were met by Robert Rainwater, the winery’s affable sales manager. “Let’s start in the vineyard,” he offered. We climbed into a dusty Dodge Ram and returned to Meyers Grade Road for a short stretch, before Robert steered us onto a private road that dove even deeper into the trees. Somehow, we were soon sharing our life story. Robert is the kind of guy who is immediately disarming. For the next two hours, we laughed a bunch.

“Do you get any mountain lions back up in here?” I asked, as Robert drove us in a pickup truck through the forest.

“Oh, I’m sure they’re up in here. Bobcats, too.”

He steered us into a clearing and there, draped over very steep and very brittle hills, were rows of emerald vine. The vineyard had a unique look to it: knee high grass, almost like wheat, tickling every row.

Lester and Linda Schwartz bought this land in the late 1980s. Originally from South Africa, they had been living in San Francisco but aching for a return to rural life. Creating a winery wasn’t their top ambition at first, but by 1991 they planted vines and Linda soon attended viticultural school. Much of the pain-staking labor — the installation of irrigation and a retaining pond, the building of trellises, not to mention tending the vines — they did themselves.

At the time, cool-climate Pinot Noir and Chardonnay in the New World were not as in vogue as they are today, and only one other prominent winery — Hirsch Vineyards — was operating along the coast. And yet, they saw something in this place to keep going.

Today, they have been joined by dozens of other vintners who have successfully capitalized on the cool-climate wine renaissance on the West Sonoma Coast. But the Schwartz’s are the only ones with a public tasting room here on the coast (it only opened in 2012), which makes their wines more accessible to travelers heading up Highway 1. In fact, many of the West Sonoma Coast and Fort Ross/Seaview wineries insist on selling their wines exclusively to a member list, with carefully monitored “allocations” that create exclusivity. They want a commitment to a club before you’ve even had a taste. In fact, I contacted Fort Ross Vineyard for this tour largely because they did not structure their business this way.

I asked Robert about this business model trend, and he deferred, preferring to emphasize the positive of being traveler-friendly. “We’re hoping to start guided tours of the vineyard soon. The more we can bring people up here, the more they’ll form a connection to the wine.”

As we surveyed their now 50-acre vineyard, we could see light-green mesh netting had been wrapped around certain rows to protect the just-ripening grapes from deer and birds, who treat the vineyard like a personal pantry. Soon, Hailey spotted a pair of cedar waxwings in an adjacent tree. These beautiful birds — whose tails look like they’ve been dipped in yellow paint — eat berries voraciously. At that moment, however, they were trying to snatch bugs on the wing.

Netting 1, Birds 0.

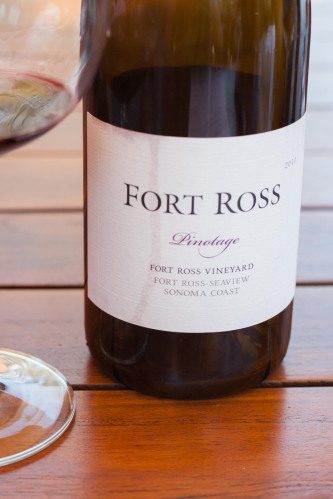

Twenty-five of 33 vineyard blocks across the estate are planted with Pinot Noir. The exception would be seven blocks for Chardonnay and a single block for Pinotage, which Robert pointed out to us as we circled around the northern end of the vineyard.

A genetic cross between Pinot Noir and Cinsault, Pinotage hails from South Africa and has never really gained traction with wine-growers elsewhere in the world. I have only had it on a couple of occasions, enough to know that it left zero impression on me. Whether it was national pride or a love of the grape, I didn’t get a chance to ask the Schwartzs. But the difficult pitches and tricky climate meant that any wine coming from this vineyard better be worth the labor and dedication.

“We’ll try some when we get back to the tasting room,” Robert added. “It’s quite good.”

In the Chardonnay blocks, the grapes looked nearly ripe, but the Pinotage and the Pinot Noir were in the middle of veraison, a beautiful state in the ripening of clusters whereby some berries have turned blue, and others are coming up from behind, still tight and green. Thinking back to the grapes in the Arista vineyard just two days before — which had been entirely dark and purple, their skins already textured with speckles — it was visual proof how drastically different the Fort Ross/Seaview area is than the Russian River Valley. A week later, harvest would start at Arista; here, it was still five weeks away.

And these would not be dense, concentrated wines. The cooling presence of the nearby ocean and its companion, the fog, wouldn’t allow it.

We rounded back to the southern end of the vineyard, where a lone oak tree crowns a hill and takes in views of the fog line below. From here, Robert painted a picture of what the fog is like over a 24-hour period with an outstretched arm, illustrating how it reaches up the valley, rolls over the hills at night, and retreats via the same path in the morning. It’s virtually the same every day, and if Pinot Noir and Chardonnay like one thing, its to consistently have a good night’s rest. Cooling off in the fog after a busy day ripening means the sugars and acidity stay in balance throughout the growing season.

You can only look at so many vines before you start to get thirsty: so we returned down the dirt road to the tasting room in the woods. Robert began by pouring three Chardonnay — the Fort Ross Vineyard cuvée, the Mother of Pearl single block, and the Bicentennial Chardonnay, which commemorated the 200th anniversary of the coastal Russian settlement from which the winery gets its name.

Each one was pleasant and enjoyable, with the cuvée being a great go-to Chardonnay for parties and mingling. But I found the Mother of Pearl Chardonnay (★★★★ 1/2) to be superb, with perfumey aromas of white flowers and orange, and hints of pear on the palate. Sourced from the highest vines in the vineyard, its grapes get all the climatic benefits, and it showed.

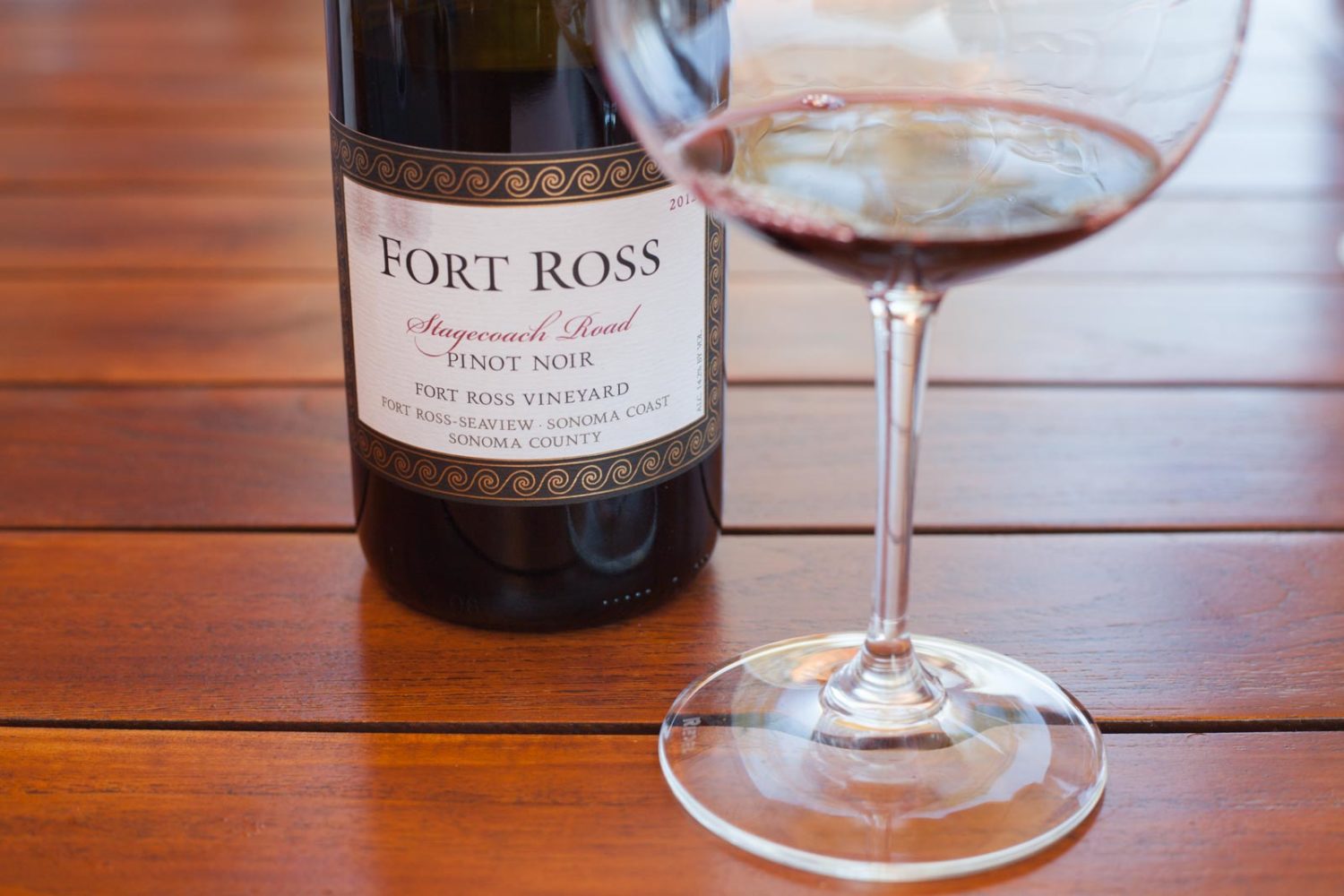

We then sampled two Pinot Noir — the Bicentennial and the Stagecoach Road. Both presented high-toned aromatics of violets and roses, as well as low notes of underbrush and leather. They seemed to be communicating nature’s work more than anything else, which I find is the single best reason to splurge on cool-climate Pinot Noir. They can’t hide anything under a veneer of ripe fruit. Instead, you detect individual elements from the vineyard. The Stagecoach Road Pinot Noir (★★★★ 1/2) in particular had a bundle of flowery notes I had not encountered before. It was a wine I’d like to spend more time with.

But, we had a Pinotage to taste as our finale. And like the Trousseau Noir at Copain, it reinforced how wonderful California’s “experimental” wines can be in the right hands.

The knock on Pinotage is that it often has off-putting aromas akin to paint or turpentine. (Ouch.) Oz Clarke suggested that South African winemakers had increasingly shied away from its New World character because they aspired for Old World characteristics in their wine.

Perhaps Pinotage hasn’t benefitted from a site as climatically gentle as Fort Ross, because this wine was fabulous, and it certainly didn’t strike me as New World in character — that is, rich, jammy and in-your-face. It was similar to a Pinot Noir in body, acidity and overall food-friendliness, but offered darker fruits, black pepper edges and a wonderful minerality on the finish. Again, it seemed to communicate what nature was saying. And it would be the one bottle I stashed in my luggage for the flight home.

As we left Fort Ross Vineyard, destined for the Sea Ranch Lodge for the last two nights of our vacation, we descended back down into the fog. At first, rays of sun cut through the gauze, creating a dramatic interplay of the elements. But as we drew closer to the sea, the fog would win the battle. We’d spend the next 48 hours in fog.

It’s pretty up there on the Sonoma Coast. Just bring a sweater.

2011 Fort Ross Vineyard Pinotage

Fort Ross-Seaview AVA

Fort Ross-Seaview AVA

Grapes: Pinotage (100%)

Alcohol: 12.5%

Rating: ★★★★ 3/4 (out of five)

• Aromas, Flavor & Structure: ★★★★ 1/2

Food-friendliness: ★★★★★

Value: ★★★

Tasting notes: Imagine a Pinot Noir with an inky-purple complexion, blackberry fruit instead of cranberry, and a black-pepper and mineral edge to it. This wine displays gorgeous, hard-to-ignore aromas: blackberry, plum, spice, wet rocks, and a trace of salumi. Deceptively light and food-friendly, it brings a great deal of complexity to the table. Finishes with a direct, lingering mineral note.

Recommended for: Strong enough for lamb, balanced for roasted vegetables. An impressive, food-friendly wine that will surprise your guests if you have them tasting it blind.

Find a Bottle of Fort Ross Vineyard Pinotage

Most wine writers seek the same thing: answers. Easy, clear, and tested resolutions to their theories. It’s why they drink so much: they believe that the more they consume, the closer they will get to understanding patterns and profiles in a wine. Read more.

On a trip to explore the northern end of Sonoma — an area I thought produced the most interesting wines for my taste — we were unwittingly beginning our journey on the extreme southern fringes, in Carneros. Read more.

It’s a refrain you hear a lot from winemakers: great wine is made in the vineyard, not in the winery. But behind Ben’s comment was a subtle suggestion that while trends come and go, what he and his family were doing with Arista’s wines will endure. After all, he was just working with what nature was dealing him — and nature knows a thing or two about being timeless. Read more.

I wanted to visit Red Car. A month before, their Sonoma Coast Chardonnay blew me away. For me, it was a rare thing: a Chardonnay without noise. There was a purity in the fruit, and a restraint on the oakiness that really allowed for some compelling secondary aromas. Read more.

Wells Guthrie’s Copain Wines had been popping up in front of me at wine shops, wine lists, wine events and wine articles for years. The word was always positive: “This guy gets it,” one wine shop owner had told me. “He has an Old World style with New World terroir … his wines are very food-friendly.” Read more.

Part 5: Fort Ross (you are here)

7 Comments