If you were to ask any wine professional to write down the 10 most important wineries in the world, how many would include Biondi-Santi?

My guess? A majority of them. For Biondi-Santi forever changed the trajectory of a little town called Montalcino, and in so doing, changed the trajectory of Tuscan wine — and Italian wine as a whole — on the global stage. Long before Super Tuscans “put Italy on the map” (one of the wine world’s most erroneous fairy tales), Biondi-Santi was winning plaudits abroad for their singular expression of Montalcino’s home-grown grape variety, Brunello, a unique biotype of Sangiovese.

The line between our taste and the reputation that brought the wine to fruition is very blurry.

What is all the more impressive is the staying power of Biondi-Santi’s legacy. From the 1850s — when a pharmaceutical graduate from the University of Pisa named Clementi Santi started to tinker with red wines at Tenuta Greppo — to the present day, the winery has rarely missed a beat. As a result of its reputation, a bottle of the latest vintage of Biondi-Santi’s Brunello di Montalcino debuts at around $230.

For many of us, tasting Biondi-Santi is a prominent bookmark in our wine career. It is impossible to see these wines as merely a drink, for — like Domaine de la Romanée-Conti or any of the Bordeaux First Growths — each sip is an invitation into the winery’s story. The line between our taste and the reputation that brought the wine to fruition is very blurry.

I was recently granted a private tour of the winery and a tasting of the latest Rosso di Montalcino, Brunello di Montalcino and Brunello di Montalcino Riserva. Here’s what to expect when your moment with Biondi-Santi arrives.

3 Reasons to Seek Out a Bottle of Biondi-Santi

- An Encounter with Italian Wine Royalty – No other winemaking family in Italy has the singular association of a place quite like Biondi-Santi, for they were the ones to breathe life into Brunello and take it mainstream. While their descendants have sold the property and are no longer involved, these wines still carry some of the family’s gravitas.

- Fads Come and Go … Biondi-Santi’s Style Has Not – It cannot be easy to stand firm on a traditional approach as the world’s sense of taste changes. But that’s what Biondi-Santi has done throughout its history. Did it blend white grapes into the formula in the late 19th century? No. Did it seek out overripeness and firmer oak when the 1990s called for it? No. And did they support adding international grapes to the Rosso di Montalcino when other producers pleaded for it? Well, almost, but no. This estate has seemingly had a force-field surrounding it as the world’s fickle sense of taste has veered away and — undoubtedly — returned to it. Whether they can keep this up for decades under relatively new ownership remains to be seen, but I think the odds are actually in their favor.

- This is the Brunello All Others Are Measured Against – Because of its steady reputation over many vintages, Biondi-Santi is often mentioned as the gold standard and the bellwether in the same breath.

About the Winery’s History

The original demand for wine in Montalcino stemmed from the village’s position along the Via Francigena, the historic road for pilgrims into Rome. The first documentation of a wine industry in Montalcino comes from the Middle Ages, but it was a sweet white wine from Moscadello that put it on the map. Records of the name brunello — the diminutive “dark one” among the area’s grapes — circulate in the late 18th and 19th century, but information on these wines is spotty.

The Emergence of Brunello

What is certain is that brunello becomes Brunello with Clementi Santi, the grape’s first ardent champion.

Santi was a noted natural historian but also a pharmacist (there should be book on all the great Italian pharmacists who double as winemakers). His estate, known as Tenuta Greppo, lied immediately south of Montalcino, on a lovely sun-dappled slope seemingly predestined for viticulture. Today, Biondi-Santi is often referred to as Biondi-Santi Tenuta Greppo as an homage to the synthesis between the pioneering family members and the hallowed vineyards of the property.

Santi was a visionary well ahead of his time. During the 1860s — when the cultivation of Tuscany centered on mixed agriculture, largely out of necessity — Santi had his intellect focused on fine wine. His research, experiments and bountiful writings elucidated the future of Brunello di Montalcino well before anyone. He preferred monoculture over coltivazione promiscura, pushed for later harvests to optimize ripening, and shunned the practice of blending white grapes with red to “soften” the wine. In the cellar, he strived for longer maceration to build structure and ensure endurance. He implemented racking to help remove sediment, and patiently waited for his wines to mature in barrel longer than what was typical of the time.

All of this was in service to Brunello, the biotype of Sangiovese that was believed to be a distinct variety, but which was undeniably linked to the little hilltop town and the sporadic vineyards surrounding it. Santi’s efforts garnered praise and momentum for Brunello built among Montalcino’s producers.

The Family Trait of Innovation

Santi passed away in 1885 and was succeeded by his grandson, Ferruccio Biondi-Santi. According to Kerin O’Keefe’s thorough accounting of the family history in Brunello di Montalcino: Understanding and Appreciating One of Italy’s Greatest Wines, Biondi-Santi was less prolific with his writing, but no less dedicated to advancing Brunello. His use of massal selection is largely credited with isolating the best performing clones of Brunello. You can dive down the rabbit hole of the famous BBS-11 clone in other literature, but the important point to know is that well over a century ago, the Biondi-Santi family was scrupulously analyzing their plant stocks for performance, a familiar trait that would carry forward well into the 2010s.

In 1917, Ferruccio Biondi-Santi passed away, leading to the estate’s succession by his son Tancredi. Widely credited as the man who would solidify Brunello di Montalcino’s place in Italian wine history, Tancredi had incredible foresight. He instituted an on-property library of Biondi-Santi’s vintages as a means to demonstrate their longevity. When World War II came to Tuscany, he walled off the archive of bottles to protect them from plundering German soldiers.

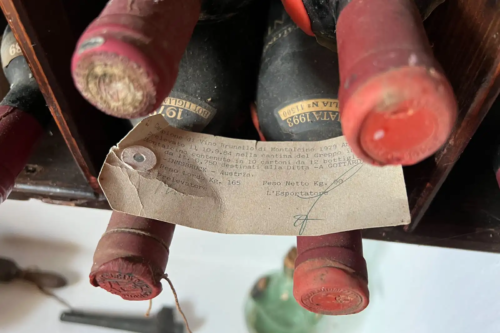

From this treasure trove of vintages, Tancredi Biondi-Santi created a program that — seen in the light of today’s modern collector — was a stroke of marketing genius. In 1927, he began to top-off older vintages of Biondi-Santi wines with their companion vintages from the family’s collection. As wine ages, miniscule amounts evaporate. Tancredi figured out a way to replace what was lost with select wines from his cellar. Today, the process is limited to only vintages of the Brunello di Montalcino Riserva, and it is rigorously implemented to guard against fraud and to protect the wines. (Only collectors with the deepest of pockets can afford it, too). But because of this unique and historic program, Biondi-Santi wines are allowed to have a vertical DOCG fascetta label on the neck so that the fill-line can be seen.

By the time Franco Biondi-Santi took the reins of the estate in 1970, an impressive legacy was in place. But it was far from certain whether it was assured. Lying ahead of him, Franco would need to protect Biondi-Santi — and Brunello in general — from the intense pressures of the new international marketplace for wine (read: here comes the Cabernet!) as well as the temptations of modern chemical agriculture. Both avenues would have represented an easier path to bigger profits in the short term, but Franco fiercely defended the primacy of Brunello and the traditional way of coaxing it into form in the cellar.

Yet, but all accounts, he was not a man of stasis. He thoughtfully considered whether the entry-level Rosso di Montalcino could allow for some blending under Consorzio rules, before ultimately voting against it. And he continued the family tradition of embracing forward-thinking research. These efforts paid off enormously for the estate, as it would retain — and even extend — its reputation into the new millennium.

The Future of Biondi-Santi

Franco Biondi-Santi passed away at 91 years of age on April 7, 2013. Three-and-a-half years later, his son Jacopo would sell controlling interest in Biondi-Santi to the French company EPI, which — among other holdings — owns Charles Heidsieck and Piper-Heidsieck Champagne. While the break in the family lineage may alter the lovely story of Biondi-Santi, it has potential upsides for these wines. Tuscan-born Federico Radi has assumed the mantle as winemaker. With important stints at two Chianti Classico estates — Villa Mangiacane and the iconic Isole e Olena — he has become a Sangiovese whisperer of sorts.

In my conversations with him last spring — as well as Sabine Cappelli, who represents the estate’s hospitality — I got a sense for the new ownership’s commitment to evolution and adaptation in the face of Montalcino’s most serious challenge: climate change. Every Italian wine appellation must adapt, but the stakes are among the highest in Southern Tuscany, where summers have grown increasing dry and hot. In the wrong hands at numerous other Montalcino estates, this trend has made Brunello (even from the famed BBS-11 clone) unrecognizable from higher alcohol and stewed fruit flavors.

“We have to keep, as much as we can, the good acidity and the low alcohol,” Radi told me. “Between 13.5 and 14% [ABV], no more than 14%.”

That’s a laudable goal, but will be difficult to achieve without substantial changes in the vineyard. Changes such as how the vines are trained, how biodiversity is maintained and even enhanced, and which clones are selected for future vineyards. As iconic as BBS-11 has been, it too may need a second look as weather patterns skew toward higher average temperatures and shorter ripening windows.

“These challenges we will be facing for decades,” Radi told me. “We have to change our way of managing, and that begins with the soil … I strongly believe that regenerative agriculture will help us to mitigate the climate change effect.”

Regenerative agriculture goes a step beyond organic or even biodynamic viticulture, by introducing the goal of being carbon-negative through the building of organic matter in the soil, usually with the introduction of farm animals to the vineyard. Radi noted that when he joined Biondi-Santi, he was surprised to learn that the soil’s organic matter was as low as 0.3%. He wants to increase that to 2% within his first 5 to 10 years. “Trying to achieve the natural balance that we should have is not easy,” he told me. “A single pass with the tractor could destroy what you built [in the soil] for two years.” (He also referred to tillage as “a hurricane for worms.”)

With increased organic matter comes an increase in the retention of moisture, which will be essential if current climate patterns become the norm. For instance, from May to September 2021, Montalcino only saw 125 millimeters of rain.

While the roots constitute 85% of the vine, what happens above ground also needs some adaptation. For that, Radi has implemented a new, V-shaped trellising system. Generally speaking, Sangiovese builds complexity with a longer ripening season. The warmer the vintage, the quicker the grapes ripen, and the shorter the maturation window becomes. (In other words: Bye-bye, complexity).

But growers also have to account for climate change’s sudden bursts of intense moisture, and Sangiovese is particularly prone to powdery and downy mildews as well as botrytis. This system, Radi believes, allows for sufficient aeration, while also providing the necessary shade to slow down the grape’s ripening.

Of course, imposing a new vine-training system takes time, and positive results are not assured. But Radi’s ambition and foresight struck me as a natural next step — not just for an iconic brand, but for Brunello di Montalcino as a whole.

Vineyard Holdings

If Radi has an ace up his sleeve, it would be the land his vineyards reside on.

For one, the 150-hectare property of Tenuta Greppo (of which only 26 hectares is vines) resides on a balcony-like ridge less than a mile southeast of the village. Its position takes full advantage of the morning and midday sun, but its high elevation ensures cooler night temperatures for balance. An apron of forest also wraps around the property on three sides, which provides biodiversity and can have an additional cooling effect at night on certain parcels of vineyard.

In order to achieve its most complex, most aromatic, most built-for-the-long-haul version of itself, Sangiovese requires a specific soil, known in this part of Tuscany as galestro. This is particularly important for Brunello because of the grape’s predeliction for power. If the composition of the soil leans too heavily towards clay — and more importantly, if the vineyard is too low in elevation — the resulting wine will have weight and potency, but at the clear cost of delicacy.

At Tenuta Greppo, Biondi-Santi has ample amounts of galestro to work with. The oldest vineyard — the historic heart of Biondi-Santi, and some could even say of Brunello di Montalcino — is known merely as Il Greppo. These vines date back to the 1930s.

Winemaking Process

In a nutshell, the winemaking at Biondi-Santi could be called both “traditional” and even “minimal intervention” (though I’d not associate them as “natural wines” given the Pandora’s box that term has become). For all wines, only ambient yeast can perform the fermentation, which typically lasts around 16 to 18 days in concrete and Slavonian oak. Aging of the wines take place in large Slavonian oak casks.

However, as Sabine Cappelli told me, where the Biondi-Santi of today differs from the very tradition it helped establish (and which is now widely adopted across Montalcino) is in the devotion of parcels to specific wines. Historically, the Rosso di Montalcino functioned like a second wine does in Bordeaux: a fruitier, fresher expression of the Brunello grape made only from younger vines. Older vines were used exclusively for the annata Brunello and the Brunello Riserva.

While freshness in the Rosso and structure in the Brunello remains the goal, the new team is not as binary in their approach. All parcels are harvested and fermented in the same manner, and not until the 18- to 24-month mark after harvest is their destiny in the bottle allocated. The reason for this is to have as much flexibility per vintage as possible.

When I pressed on whether — even after this approach — the older vines managed to find their way into the Brunello and Riserva anyway, Cappelli assured me that the vintage character from parcel to parcel is stronger than the vine-age character. “The idea is not to have a single cru, but to [consistently] distinguish one from the other by the details.”

Your First Taste

What do Biondi-Santi’s wines taste like? “Supreme elegance” would be one way of putting it, but that doesn’t accurately reflect the duality of these wines. They also possess an intensity and power that are the hallmark of Brunello di Montalcino. Far too often in the DOCG, wines boast of the latter without the former. Only a few wineries are able to allow Brunello the space it needs to show both of its faces, and Biondi-Santi is chief among them.

There are three wines you might taste, and they will possibly be different vintages from those I write about below (tasted on April 4, 2022). But a lot can be learned from the 2018 Rosso, the 2016 Brunello and the 2015 Riserva.

My two suggestions: do not overlook the Rosso di Montalcino. It is no mere “entry-level” wine. And secondly, be wary of drinking a Riserva too soon after vintage. It is a monumental wine that deserves time.

2018 Biondi-Santi Rosso di Montalcino

As we discussed above, the Rosso di Montalcino is fermented just like the Brunello. After 18 to 24 months, the tanks that best represent the Rosso style (i.e. fruitier, more approachable) are selected for this wine. On the nose, the complexity of that fruit is evident, with tones suggestive of ripe black cherry and blood orange coming to the fore. It is a stunner aromatically, with an easy grace as it crosses the palate. When revisited after tasting the Brunello and the Riserva, the Rosso was noticeably lighter and sleeker (as you’d expect given the cool vintage of 2018), but here is what amazed me: it was no less precise. In fact, if you were to define what Sangiovese ought to be, this wine and what it says on the nose and palate would be in the running as the bottle to do that.

After two and half weeks of fermentation, this wine spends 12 months in large Slavonian oak barrels.

★★★★★

2016 Biondi-Santi Brunello di Montalcino

The Biondi-Santi Brunello on the other hand, is the quintessential definition of what Brunello can be: more focused, more depth, more structure, and richer fruit notes, all wrapped up in swirls of leathery, mint-like aromas. I was genuinely surprised at how upfront and open this wine was given its stature and youth. Cappelli also offered a taste of the same vintage that had been open for three days, just to illustrate the wine’s ability to hold form over time, but also to allow for more open engagement with it. More expressive yet silkier, the second 2016 revealed to me how versatile this Brunello could be at the table.

After two and half weeks of fermentation, this wine spends three years in large Slavonian oak barrels. It then spends another two years in bottle before release.

★★★★★

2015 Biondi-Santi Brunello di Montalcino Riserva

So you are drinking the Biondi-Santi Brunello di Montalcino Riserva? Lucky you. Since 1888 when the first Riserva was produced, there have only been 41 vintages where conditions were ideal enough to make a Riserva at Biondi-Santi. That said, 15 of those have occurred over the last 30 years, partly because of a warming climate being more conducive to what the Riserva is all about.

If your first taste of the Biondi-Santi Brunello di Montalcino Riserva is not a clear-eyed “a-ha moment,” you are not alone. This wine is meant to be elusive, but it does a wonderful job of offering enough threads to pull you deeper into the experience. Even after the majesty of the Brunello di Montalcino, somehow, the fruit of the Riserva seemed to be even more complex and deep — the overall sensation, richer. The aromas were more closed, likely because of the wine’s relative youth, but there were tones deep within reminiscent of orange citrus, mint and leather. It seemed to be voracious as it moved across the palate, with rich acidity and coarse, cotton-like tannins that racheted up the intensity from the previous wine.

It is difficult to assess such a wine when it clearly needs more time to settle into form, so my rating below reflects how the wine presented a mere 6.5-years after vintage. However, it certainly has promise. If you can, wait another 5 to 10 years.

After two and half weeks of fermentation, this wine spends three years in large Slavonian oak barrels. Riserva wines are only released when the team at Biondi-Santi deems them so, but at a minimum, they’re held in bottle an additional three years.

★★★★ 3/4

Support the Independent Wine Writing and Classes of Opening a Bottle

Become a subscriber today to gain access to all of our virtual wine classes and to read all of our wine reviews. It’s just $9/month or $79/year, and it helps to keep stories and insights like this going.

How do you go about reserving a tour of the winery?

Tours might be reserved only for the wine trade, which is how my appointment was made, since I was writing an article. You can inquire directly with the winery or through an importer.