It might seem like you need a post-doctorate degree in the European Middle Ages to understand the history of Chianti Classico. After all, not only is it among the first wines in Europe to have its name protected by law (1716), but the entire wine region was once the rope in a generations-long tug of war between the powerful city-states of Florence and Siena. The landscape we see today is equal parts a case study in terroir and a game board of Risk, with fortifications now hosting tourists instead of battalions. Wealthy land owners, disenfranchised peasants, monasteries and even Michelangelo all have their fingerprints on Chianti, and in many ways, that history — as illustrious as it is — creates an uneditable backdrop for the wine. Curious drinkers may not know the ingredients of Chianti, but they know it is an old place.

The landscape we see today is equal parts a case study in terroir and a game board of Risk, with fortifications now hosting tourists instead of battalions.

However, it is becoming increasingly clear that Chianti Classico may be one of the most progressive and forward-thinking appellations in Italy. Once beholden to an iron-clad blend that no longer fits with the times, the appellation is relentlessly redefining what it is and how it wants the world to view it: namely, as a fine wine, but also a showcase of terroir through the vessel of Sangiovese.

At its best, Chianti Classico certainly ticks both boxes. And the region’s rich biodiversity — a holdover of its history — may help preserve this trend as producers face the uncertainty of climate change.

I recently journeyed through this mountainous region between Siena and Florence, visiting 12 different wineries and documenting the distinct villages they now call UGAs (Unita Geografica Aggiuntiva). In the coming weeks, we’ll be reporting on this area’s leading wines as well as its future. But first, it is best to take a step back and understand the history of Chianti Classico. The following has been extracted from our lengthy First-Taste Guide to Chianti Classico, and together, this three-part series will bring you up to speed on everything you need to know about these savory, juicy, long-lasting red wines, and why they are the way they are.

Chianti Classico’s Medieval Origins

The hills south of Florence have long sustained a mix of agriculture. The Etruscans and Romans grew grapes here for winemaking purposes, but these wines were not renowned far and wide until the Middle Ages. Even then — and even today — viticulture represents only a sliver of the total land use in Chianti Classico. Olive oil from the area is highly regarded, and a majority of the landscape today is covered by protected forest, which helps moderate the climate and increase the area’s biodiversity. In fact, of the wine regions I’ve traveled in the world, only the extreme fringes of Sonoma can compete with Chianti Classico in terms of biodiversity.

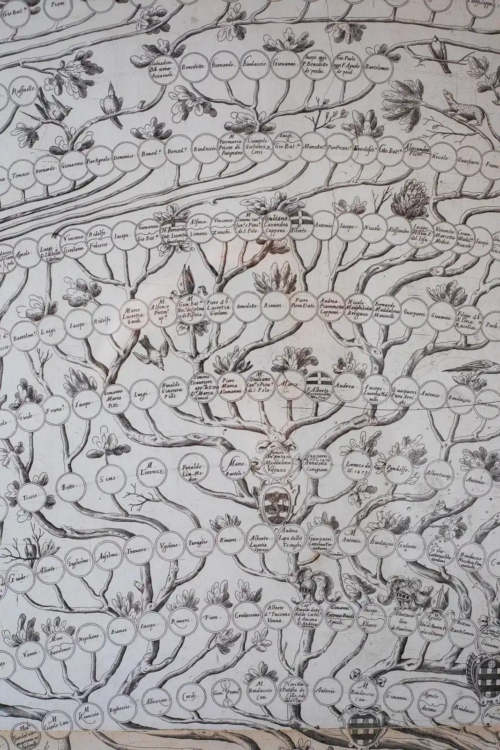

In the Middle Ages, wealthy landowners established fiefdoms across Tuscany, and Republics such as Florence, Pisa and Siena formed alliances against each other. One of these alliances was the Lega del Chianti. Established in 1384 by the Republic of Florence, it included the villages of Castellina, Radda and Gaiole, and it served as an important buffer against the rise of Siena to the south. From a military perspective, Radda and Gaiole were the high ground: once established, they could be defended with greater ease. Today, that high elevation and its brisk climate serve as “the higher ground” for terroir enthusiasts.

It was around this time as well that the mezzadria system of sharecropping began to define the rural economy. Under the system, land owners would allow farmers to tend to the land in exchange for a portion of the crop. Sharecropping would enforce the class system for centuries, eventually crumbling with rapid industrialization after World War II, as well as a government ban of the practice in the mid-20th century.

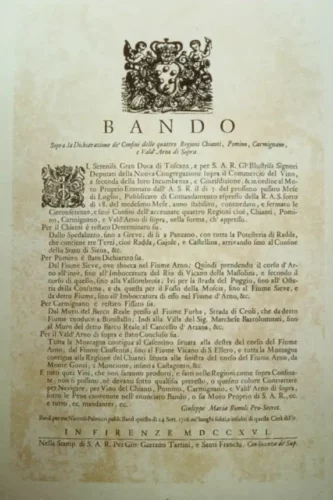

From the Middle Ages on, wine became a central part of the Florentine economy. As a means to control exports and guard against fraud, Cosimo III de’ Medici issued an edict (bando) in 1716, which demarcated the Chianti Storico zone. The bando expanded the Lega del Chianti zone to include Greve and Panzano.

The Ricasoli Blend

What constituted this wine at the time remains a subject of debate. It is believed that by the late 18th century, Canaiolo — not Sangiovese — was the central grape of Chianti’s wines.

Baron Bettino Ricasoli of Castello di Brolio started to change that in the 19th century. His tireless experimentation would be mostly a boon for the region (its misapplication, however, would eventually become a curse).

For one, he elevated the standing of Sangiovese, noting that its strong character and perfume made it essential to his blend. Canaiolo, in his opinion, was better served as a minor blending partner to soften the edges. Even today, many of the best wines in the area rely on the special alchemy between Sangiovese and Canaiolo. But Ricasoli also conditionally advocated for a swath of Malvasia to lighten the wine if it was intended for early consumption. Given winemaking techniques at the time (e.g. lack of temperature control), the addition of Malvasia was likely a smart choice — something to tame the coarseness of Sangiovese.

Below is a video of Baron Francesco Ricasoli, the current proprietor of the estate, reading the original formula, which is proudly displayed on the cellar wall at the winery. The translation is borrowed with permission from writer and Italian wine expert Jeremy Parzen (his full blog post on this now-famous passage from Ricasoli is worth the read).

This is the “formula,” and yet it is written not as an iron-clad instruction set, but rather as a conclusion from a handful of experiments. I find his wording on Malvasia particularly interesting, as he says it “can be excluded from wines intending for aging,” as it “tends to dilute” but paradoxically “increase the flavor” and lighten the wine for earlier consumption. That sounds pragmatic, and hardly formulaic.

Yet this passage turned into gospel. Despite Ricasoli’s thoughtful explanation on why Malvasia could (not should) be used, white grapes came to represent between 10 and 20% of future blends across the region. Problematically, many substituted Malvasia with Trebbiano, a more productive grape that further diluted the final blend.

Just as significantly: the Ricasoli Blend became vogue outside Chianti. From Pisa to Pistoia to Arezzo and south to nearly Lazio, producers were adopting this very blend, but cutting corners. And the terroir of many of these vineyards proved to be less than ideal for the anchor grape, Sangiovese: in some cases, too warm (higher alcohol, off-balanced tannins), in other cases, the wrong soil (too much clay equaling too much water retention equaling too much vigor equaling dilute wines).

Others mixed in an even larger share of white grapes. Nearly all of them called this wine “Chianti” or “Vino all’uso di Chianti.” And just like that, the name Chianti was transferred from provenance to product. To this day, they’re still trying to claw that back.

The Establishment of the Consorzio

In 1924, 33 producers from the heart of Chianti banded together to form the first Italian consortium of winegrowers — today known as the Consorzio Vino Chianti Classico. Their hope was to protect the brand of Chianti before it completely slipped through their fingers. They adopted the gallo nero (black rooster) as their trademark, a symbol that continues to be displayed on the neck of every Chianti Classico wine.

But then the Italian government struck a blow to their branding efforts in 1932. In an effort to cull wine fraud, they defined Chianti as a wine from a broader range of hills in central Tuscany. The concept of subzones was instituted, creating a cadre of Chianti-named wines from divergent terroir: Chianti Rùfina, Chianti Colline Pisane, Chianti Colli Aretini, and so forth. (And here is an important note in light of recent developments: subzones are larger and more broad than the UGAs recently codified in Chianti Classico).

Of these subzones, the heart of the region — the very birthplace of the name and the wine, and to many, the ideal terroir for Sangiovese — would be known as Chianti Classico.

This decision continues to confuse consumers. Imagine if every Nebbiolo wine had the word “Barolo” appended to the front of it: Barolo Lessona, Barolo Gattinara, Barolo Roero, and so forth. If this were the case, Barolo would be known as a product and not a place with a unique terroir. Such is the case with Chianti’s historic heart, and — oddly enough — for many fine producers from the Chianti subzones, who have expressed a desire to shed the Chianti moniker and be know as, for example, just Rufina.

The greater Chianti appellation would be granted DOC status in 1967, with a loose interpretation of the Ricasoli formula serving as the regulated guideline for winemakers (allowing for an astounding 30% white grapes!). The DOC status, plus the end of the mezzadria system, generated increased plantings. But in many cases, the quality of the wines suffered due to poor site-selection and the ubiquitous use of Trebbiano in the blend.

Chianti became synonymous with cheap wine in wicker-basket bottles known as fiascos. To a generation of wine drinkers, these bottles weren’t seen as an ideal for fine wine — they were just an ideal candlestick holder for dorm rooms and pizzerias.

The Modern Era

Meanwhile, on the Tuscan coast, a not-so-little wine called Sassacaia was redefining the landscape, and showing the world that Italian red wines could rival those from anywhere, particularly Bordeaux. Sassacaia proclaimed on the international stage that Italians could once again make some of the world’s finest wine. It undeniably put pressure on winemakers across Italy to improve their quality, but especially in Tuscany.

Inside Chianti Classico, producers were beginning to revolt against the outdated guidelines that were holding their wines back. They explored varietal Sangiovese. Some planted Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot for blending. Others adopted small French-oak barrels for aging their wine. And many started to drop the name Chianti Classico entirely from their label so that they could — ironically — make better wine.

These wines became known as the Super Tuscans, and their success on the international marketplace in the 1970s, ’80s and ’90s forced the consorzio to change its tune. Stricter standards were adopted for yields, white grapes were diminished in the blend (and then eventually banned in 2006), and 100% Sangiovese was allowed. By 1996, Chianti Classico was separated from Chianti and awarded its own DOCG. (Side note: You will note that all Chianti Classico wines boast the black rooster logo on them — a vital clue for consumers in a sea of Chianti options at their local liquor mart).

Furthermore, a campaign to better understand the different clones of Sangiovese was also launched, providing important research to match the grape’s diversity to Chianti Classico’s diversity of terroir. We are only just now seeing the fruits of these efforts.

The Way Forward

Chianti Classico is steadily reclaiming its spot in the pantheon of Italian wine.

But the changes — as well as the introduction of the Gran Selezione category in 2014 — didn’t remove the most important sticking point: Chianti Classico vs. Chianti. Ironically, the original decision was based on which regions were using the Ricasoli formula. Today, hardly anyone is using it.

What’s keeping the authorities from restricting the word “Chianti” to only “Chianti Classico?” One assumes its a word that starts with M and rhymes with “honey.” The glut of mass-produced Chianti wines from the rest of Tuscany generates huge revenue.

But for those who take the time to understand the differences, the rewards are there. Chianti Classico is steadily reclaiming its spot in the pantheon of Italian wine. There are still a few obstacles, namely the continued use of Merlot and Cabernet Sauvignon in the blends at some estates, a practice which quickly renders Sangiovese’s unique voice mute. Heavy-handed oak aging can do the same. But at more and more estates, I am seeing reasons for optimism. An increased interest in terroir-sensitive wines, and an embrace of organic viticulture is yielding fascinating results. This last part may be the most promising piece of news: a majority of Chianti Classico’s vineyard land is certified organic. That’s right: I said “majority” and I said “certified.” That’s unheard of.

As wine consumers take an increased interest in the origin of their wine — and particularly the care and environmental health of the vineyard — Chianti Classico offers a great deal to them.