History and tradition are often a force for stasis. However, despite being one of the first places in the world to legally protect the name of its wines, the Chianti hills in between Florence and Siena have never been static. Throughout its winemaking history, the region that makes what we now call Chianti Classico has produced white wines, blended red wines with white grapes, blended red wines with indigenous and international varieties, and — most recently — a wealth of varietal Sangiovese.

All of these permutations provide context for the moment Chianti Classico finds itself in now, for the appellation is turning the page on yet another new chapter. An extensive, multi-year effort to map and zone the 11 villages of the DOCG appellation has resulted in a codified plan to allow village labeling on the front of the wines, starting with the highest-end category, the Gran Selezione. The message of this effort is loud and clear: Chianti Classico has terroir worth celebrating.

The message of this effort is loud and clear: Chianti Classico has terroir worth celebrating.

But as I found out when I spent several days in the area this spring, nothing is simple in Chianti. If your goal is to express a sense of place in the glass, you need to strip away a lot of variables and find focus. From grape selection to microclimate to winemaker ethos to oak usage, Chianti Classico can sometimes seem like nothing but variables.

What follows are a series of producer profiles that demonstrated to me how Chianti Classico is honing in on a terroir ideal. Yet, these visits also raised questions about what we stand to lose if terroir becomes a crutch to oversimplify this complex place.

Ricasoli: Reconciling Tradition with Modern Taste

“Winemaking, viticulture and even human culture are changing constantly,” said Baron Francesco Ricasoli, the proprietor of Ricasoli 1141, the oldest continuously operating business in Italy. We were chatting in the sitting room of his winery’s headquarters as it darkly rained outside. It was too wet to stomp through vineyards, but the atmosphere seemed perfect for tracing Chianti’s past to better understand its future.

I had asked Ricasoli for a personal definition of Chianti Classico — what it meant to him and his family. His answer was guaranteed to be unlike anyone else’s, because in 1872, his ancestor, Baron Bettino Ricasoli, pioneered a blending formula that would serve as the basis for Chianti’s identity for generations to come [view a video of Baron Francesco Ricasoli reading the formula in our article, Understanding the History of Chianti Classico].

Today, that blend and its white grapes have been ditched in favor of a hodge-podge of all-red blends and, increasingly, 100% Sangiovese. In fact, of Ricasoli’s eight different Chianti Classico wines, all but two are now varietal Sangiovese.

If the company is so proud in its role establishing the blending formula, why no longer use it? I asked.

“The habits of my ancestors were pretty different from mine, and they will be pretty different from the one my daughter will inherit. Having said that, I think that our duty — especially in a family like ours — is to be contemporary. We cannot live out of the past, but we have to live out of the future.”

His answer neatly encapsulated why Chianti Classico is always changing. And increasingly, that contemporary outlook is an exhalation of Sangiovese — not so much because of its power, its savory quality or ageability (as it was prized for in the past) but rather because of its ability to transmit terroir.

“It is not a scientific classification, but at least it gives us the reason to do more fine-tuning inside the region.”

Baron Francesco Ricasoli

President, Ricasoli 1141

Ricasoli is the Vice President of the Associazione Viticoltori di Gaiole, which organizes and promotes the wines of the village of Gaiole. It is among the largest and most varied communes in Chianti Classico. Generalizations won’t work here. So, with pointer in hand and vials of distinct soils, the Baron gave me a tutorial on Gaiole’s varied geology. For him, the clearest evidence of terroir can be found in his Gran Selezione, particularly the single-vineyard wines named Roncicone, Ceniprimo and Colledilà. Side-by-side, these three powerhouse wines offer subtle contrasts thanks to the restrained use of oak. But would I be able to peg them as Gaiole instead of Radda or Castelnuovo Berardenga? Over time, perhaps. But for now, I — like a lot of wine professionals — had a lot of comparison tasting to do before that “a-ha moment” arrived.

“It is not a scientific classification,” Ricasoli admits. “But at least it gives us the reason to do more fine-tuning inside the region.”

Rodáno: Adapting to Change While Staying True

At Fattoria Rodáno, the rain once again forced us inside. One-hundred precipitation-free days had preceding my visit to Chianti Classico, so no one — especially winemaker Enrico Pozzesi — was complaining.

“There is no other place that is like Chianti Classico in the world,” Pozzesi told me, with a tinge of adoration in his voice. “The forest … the olive trees … the Sangiovese.” This last item he said with a gentle relish.

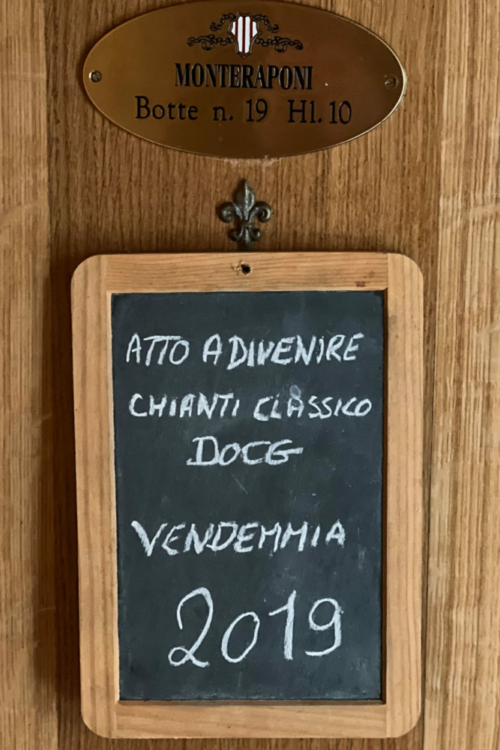

Pozzesi is a student of Giulio Gambelli, a famed Tuscan enologist who redefined Sangiovese wines from the 1970s until his death in 2012. The Gambelli connection explains some of Pozzesi’s devotion to the old-school way of making Chianti Classico. That means no international varieties in the blend, and an ethos focused on capturing Sangiovese’s purity in the winemaking process. Surrounding us in the cramped space were large, 25-hectoliter oak casks for just this purpose. These botti, as the vessels are called, gently integrate oxygen during élevage. They also lack the woody tannins and oaky flavors of new barrique and tonneaux barrels, which unquestionably muffle Sangiovese’s beautiful, raspy voice.

This setting may not sound like “the future of Chianti Classico,” but Pozzesi is in many ways the perfect embodiment of this moment. “Someone says Rodáno makes traditional wine,” he noted. “You know, I think ‘traditional Chianti Classico’ has no meaning.”

That is because everything is constantly changing: if it is the nature of Chianti Classico to be dynamic, what is “tradition” in the first place?

He then proceeded to list the many ways the script has been rewritten over his 40-year career, from yields to categories to climate change. This was not grievance; it was just fact. And while he is proud of the terroir in Castellina — and would love nothing more than his customers better understanding it — he was reluctant to embrace the Gran Selezione category for his most terroir-centric wine, the Vigna Viacosta Riserva.

“For me, the most important thing is to make a good regular Chianti Classico,” he said, referring to the entry-level annata category. “My dream is Chianti Classico without category, but I think that the reality is completely different.” He told me how he tried to sell the Vigna Viacosta without the Riserva label, but customer demand for Riserva wines — and the need to recoup his costs from aging the wine for three years — meant he needed the category as well. Consumers were not interested in paying a premium for “entry-level.”

But he disagreed with the idea that the categories were a quality pyramid. “I see nothing wrong with Gran Selezione,” he made clear. “The problem is that 20 years ago, the idea of making Chianti Classico was to make a wine like Bordeaux. Maybe now there are some producers that have this problem: maybe now they understand that with Sangiovese you can make the best wine with this terroir. But I don’t know how much they believe it. Sometimes I taste some Riserva and Gran Selezione, and I can say ‘ok, the wine is a very good wine. But is it an expression of terroir?’ Sometimes yes, sometimes no.”

“I think the future will be Sangiovese alone. We still have to blend with some Canaiolo and Colorino, but the reason that Chianti Classico was a blend of different grapes is no longer necessary.”

Enrico Pozzesi

Winemaker, Fattoria Rodáno on climate change altering Sangiovese

At the recent Chianti Classico Collection in Florence — an annual tasting event for the trade — Pozzesi noted that people’s attention passed over the regular Chianti Classico, going straight for the prestige wines of Riserva and Gran Selezione. “I am a producer, but I am also a consumer. I buy a lot of wine. The first thing that I buy from a seller is the first-level wine. If it is good, I can go up.”

And this is where things get a little upside down in Chianti Classico. The wines that often showcase village terroir the best are the entry-level wines: they are fresher, less oak influenced and capable of transmitting some of the broad-stroke hallmarks that might allow wine lovers to celebrate a place like Castellina. The more structured and age-worthy Riserva and Gran Selezione wines — if done without too much oak influence or international grapes — can certainly showcase terroir, but often at a more specific level, such as the Vigna Viacosta, or Ricasoli’s trio.

Yet for now, only the Gran Selezione category will be allowed to bear a village name.

Every producer I met had firm opinions on the three categories of Chianti Classico, but I wouldn’t call any of their positions acrimonious. Their freedom to use the categories in a way that meshes with their philosophy is entirely up to them, and the same goes for the decision to blend grapes or aim for a solely varietal Sangiovese. It was on this topic that Enrico Pozzesi noticed the biggest changes in Chianti Classico — changes that go well beyond the power of the producers and Consorzio — as he notes in this video.

While the volatile changes in climate are alarming on many fronts, the consistent trend of warmer temperatures presents opportunity on another. Canaiolo was known for softening the abrasive edges of Sangiovese. Those edges have been polished by greater degrees of ripening in Sangiovese. Colorino earned its place in the vineyard by lending color to the blend, but that too has been largely rendered moot.

Whether borne out of desire for simplifying the vineyard and cellar work, or a belief that varietal wines showcase terroir differences better, producers have increasingly gone all-in on Sangiovese. Yet a few outliers — Rodáno included — continue to show the value of these grapes and their ancient alchemy with Sangiovese. It wasn’t until my visits and tastings were complete that I noticed a peculiar trend in my reviews: a large share of the wines I rated highest were blends of native grapes with Sangiovese. Clearly, characters like Canaiolo and Colorino still offered something to the script in Chianti Classico.

Monteraponi: Following Burgundy’s Footsteps (or Not)

The influence of Bordeaux and Burgundy is hard to ignore in Chianti Classico. Estates seem evenly split on whether to embrace power and structure, as well as oak-influence and blending (ahem, Bordeaux), or to adopt the elegance of a singular voice that speaks of terroir (e.g. Burgundy). Undoubtedly, the shift toward establishing villages (also known as UGAs, an acronym for “additional geographical units”) shows a desire to pursue the ideals of the latter.

As my travels progressed, I started to make notes on the stemware producers offered at their tastings, and whether it was a bellwether of their philosophical approach. It usually was.

Few villages produce a wine more appropriate for Burgundian stemware than Radda, where rocky terrain and cooler evening temps seem to bring out a heightened aromatic character to Chianti Classico. One Radda winemaker aspiring for elegance (and largely succeeding) is Michele Braganti of Monteraponi. He was not shy on how he thinks Chianti Classico stacks up to Burgundy.

“We are lucky in Tuscany because we have more. The soil, the history, the culture, the [bio]diversity,” he said. This last factor is one of Chianti’s best attributes, as most of the area is locked away as forest — a trait that helps cool vineyards at night. “Honestly, I’ve been to Burgundy. It’s not a fantastic land like the Chianti Classico. It’s just vineyards, vineyards, vineyards.”

“For me, the Sangiovese is the speech that helps to [convey] Chianti Classico.”

Michele Braganti

Winemaker, Monteraponi

However, Braganti clearly admires the wines of Burgundy and firmly believes that Chianti Classico can learn from the Burgundian model to better showcase its terroir. “We have to go beyond the symbol of the black rooster to speak about the village, the exposition, the soil,” he noted. “This does not mean that Radda is better than Gaiole, and that Gaiole is better than Castellina. They are just completely different.”

However, unlike Burgundy — where the singularity of Pinot Noir and Chardonnay afford apples-to-apples terroir comparisons — Chianti Classico remains open to blending. While blended wines can certainly showcase terroir, they shift the narrative of comparison from apples-to-apples to apples-to-apricots.

Like Pozzesi at Rodáno, Braganti continues to blend small amounts of Canaiolo and Colorino into his Chianti Classico. “I believed in Canaiolo since the beginning, because Canaiolo was on [this] hill since the beginning,” he said, motioning to the vineyards outside the window. Canaiolo and Colorino ripen earlier, and in previous generations, he explained, producers would harvest them overripe with Sangiovese and co-ferment them, a process designed to balance the coarse tannins of Sangiovese.

But, “Canaiolo is like the Colorino: it’s very difficult to grow. It gives the farmer more problems than Sangiovese. It gets sick more easily from oidium than Sangiovese.”

So why continue to work with these indigenous grapes if it is just easier to make varietal Sangiovese?

Braganti pivoted and noted that he is a believer in varietal Sangiovese at the top of the pyramid where terroir is now the focus. “For me, the Sangiovese is the speech that helps to [convey] Chianti Classico,” he said. “We have the Chianti Classico and the Chianti Classico Riserva to do everything. The Gran Selezione has to be only one, for me. It has to be 100% Sangiovese.”

And because varietal Sangiovese is not required at the “top of the pyramid,” Braganti would rather not make one. For now, the Gran Selezione category requires 90% Sangiovese, and as long as that is in place, Braganti will continue to make two — rather than three — Chianti Classico wines: his annata and “Il Campitello” Chianti Classico Riserva.

Badia a Coltibuono: The Alchemy of Native Grapes

At Badia a Coltibuono in Gaiole, the embrace of native grapes is taken to another level. Sangiovese is certainly exalted at the “abbey of good cultivation,” but the role of Canaiolo and Colorino are on equal footing with never-heard-ofs like Sanforte and Fogliatonda.

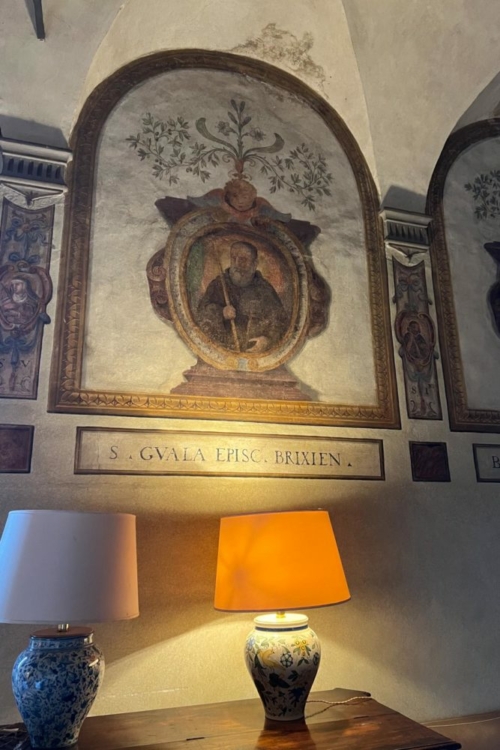

Winemaking has a very ancient lineage on the site, with archaeological evidence of the practice dating back to the 1st century AD. The Benedictine monastery founded on the site in 1051 produced wine as well as numerous other crops, and that continues to be the story today under the careful watch of the fifth-generation of the Stucchi Prinetti family, who have owned Badia a Coltibuono since 1846.

Badia a Coltibuono’s wines are among the purest and most underrated in all of Italy. The Chianti Classico and Chianti Classico Riserva wines are savory, juicy and spicy, but they never lose sight of their role at the table. And with the exception of a separate product line called Cultusboni, none of them are varietal. In fact, their second Chianti Classico Riserva named “Cultus” is only 80% Sangiovese, with the remaining portion of the blend relying on varying proportions of Colorino, Canaiolo, Ciliegiolo, Mammolo, Pugnitello, Malvasia Nera, Sanforte and Fogliatonda.

“We never went for the single vineyard. We always went in a way for grape selection. It allows us to adjust with the vintage.”

Emanuela Stucchi Prinetti

Proprietor, Badia a Coltibuono

Why? Emanuela Stucchi Prinetti told me that winemaking at Badia a Coltibuono is less about the singularity of site and grape variety, and more about achieving the right balance year after year — a very Chianti Classico ideal from the past.

“They give us an extra flexibility,” she said, referring to the winery’s wealth of native grape plantings. “Also, considering that now we have issues of too much alcohol, too much concentration [because of climate change] … to have another tool that grows in the vineyard is a plus.”

Stucchi Prinetti likened these grapes to spices, and how they season Sangiovese’s character, lending it details that Sangiovese normally does not have.

“We never went for the single vineyard,” she also noted. “We always went in a way for grape selection. It allows us to adjust with the vintage.”

For now, there is no Gran Selezione in the works for Badia a Coltibuono, which means they will not be participating in the village labeling anytime soon. Yet, when you drive up to the spectacular abbey, which is set against towering trees and sloping mountains, and where snow in early April is not an unusual sight — Badia a Coltibuono embeds in your memory as the quintessential image of Gaiole. It is the kind of impression that renders blind tastings and tech sheets silly. The terroir of the wine is as much the terroir of your memory as it is the soil and climate. Certainly that counts for something.

Istine: The Answer is Upside Down

The scenario Chianti Classico is presenting Italian wine lovers is actually quite thrilling, as many of us feel like we are starting at zero with terroir studies of the area. What does Castelnuovo Berardenga taste like? How do the adjacent villages of Greve and Lamole stack up? For so long, the overly oaked, blended wine milieu of Chianti Classico’s past had informed my baseline. While I was beginning to tease out some details, they were only in broad strokes. But I was enticed. I wanted to keep going.

For my final estate visit, I returned to Radda. Of the 11 UGAs, Radda’s rocky heights may stand out most to travelers. The village straddles a prominent ridge and on sunny days it seems to claw at the passing clouds with a patchwork apron of vineyards scattered below.

In a lineup of wines, Radda is also an early frontrunner for the most recognizable village, both because of its terroir and its community of dedicated, terroir-focused winemakers who have produced a comprehensive baseline for us to examine. Radda is not only where you will find Braganti’s Monteraponi, but several other superb estates as well, like Caparsa, Volpaia, Poggerino and perhaps the most of-the-moment winery in the appellation, Istine, where winemaker Angela Fronti gave me a quick tour of her vineyards before more rain moved in.

Fronti’s pragmatic approach to her product mix looks like an upside-down version of Chianti Classico. That’s because the entry-level wines — the Chianti Classico annata, which have the least amount of aging before release — include her single-vineyard expressions. Don’t let their ready-upon-release nature fool you: they are complex and nuanced. I couldn’t help but wonder if the details they revealed were more educational than any Gran Selezione I tasted on the trip.

Fronti’s decision to configure her wine roster this way comes from a mix of familial roots in the area, as well as an informative, 10-year-long period working away from family business, as well as outside of Radda and Chianti Classico. Unlike many wineries in the area, which trace their heritage to nobility and wealthy land owners, Istine’s story begins with its peasant ancestry. Fronti’s family were sharecroppers, the lifeblood of the agrarian economy in Tuscany up until the 1960s. Her grandfather established a farming service company in 1959, and with the proceeds from the successful business, they bought vineyard land in the 1980s. The fruit was largely sold off or used for family wine.

Fronti took an interest in viticulture, and after her degree, opted to work around Tuscany for a time, including stints with her uncle, Paolo Cianferoni at Caparsa, but also several wineries further afield, like the Syrah-focused Tenimenti d’Alessandro in Cortona.

Reflecting on it now, she says that if she had only worked for the family vineyards, she might have taken a standard approach to what Chianti Classico had been. “Maybe international varieties, maybe barrique? I don’t know [how that would have gone],” she said. “But working for other companies, I understood better what I wanted.”

That turned out to be her “favorite wine of all,” Sangiovese from Radda, a unique taste that felt personal and close to her heart. “I thought ‘I am stupid if I don’t try this project,” she said, referring to managing her family’s vineyards.

So in 2012, she kickstarted Istine, converting the estate to organic viticulture and steadily finding her way through experimentation. “To be honest, I have improved the number of bottles, the label, the overall quality,” she said. “But it’s been 10 years that I’ve been working, and maybe I am more sure, but every year I am [also] more anxious. I think people have a lot of expectations because this new winery now is not so new.”

In the last six months alone, Fronti’s wines have been featured as a “best buy” Chianti Classico in Decanter and as one of NY Times‘ wine critic Eric Asimov’s Top 12 wines of 2021. Her estate was also included as one of the top 100 Italian wineries in Wine Spectator’s OperaWine. There is good reason for this: her wines are fantastic, and offer perhaps the best glimpse of Chianti Classico’s future as a terroir-centric wine region.

“We have so much difference between each season because of the facing of the vineyards and the altitude, [that] we want the Riserva to be the best synthesis, the best harmony.”

Angela Fronti

Winemaker, Istine

As night fell and more rain swept through, we tasted the 2019s together in her winery. This was the last of 12 Chianti Classico wineries I would visit over my three days there, and here was the clearest demonstration yet of individualistic terroir at the village level. The Vigna Istine from the rocky, north-facing vineyard by the winery in Radda, demonstrated a thrilling citric tone to it that rendered Sangiovese in the crispest, cleanest of tones. The Vigna Casanova dell’Aia, from a plot directly below the village, offered a fruitier feel and lovely, chalky tannins. Meanwhile, the Vigna Cavarchione — from a vineyard holding in the adjacent village of Gaiole — showcased greater depth and a profound savoriness. Fronti noted that each vintage, these three vineyards tell something different through their wines. Even she is still trying to understand it.

Each wine is vinified separately, and then the tanks that best represent each vintage’s character are blended together for her Riserva. As I tasted the 2017 Riserva, it was clear how elements of all three vineyards came together to form a harmony that was profound and masterful.

As to whether any of her wines will someday be Gran Selezione, she has doubts. “Everyday I think about that,” she told me. “We have so much difference between each season because of the facing of the vineyards and the altitude, [that] we want the Riserva to be the best synthesis, the best harmony.” However, her vineyards straddle two UGAs, prohibiting her from elevating that wine to Gran Selezione. She also has plans to expand into other vineyards, but noted that “it makes no sense to have five Gran Selezione.”

Yet, despite this clarity of terroir, none of these wines — per the first iteration of the new UGA zoning guidelines — can qualify from village-labeling. This wrinkle doesn’t seem to phase Fronti; her wines clearly have an audience, regardless of the category they fall into. And in the end, that’s perhaps the way forward: make pure, lively and character-driven wines, and drinkers will soon follow.

Opinion: Where Should Chianti Classico Go?

The Chianti hills between Florence and Siena should not be seen as monolithic.

I visited seven other estates over those three days in the Chianti Classico zone, each one offering a new spin on where the region and its marquee wine is headed. (I’ve also spent six months sampling as many Chianti Classico wines as possible from afar). The biggest common thread I heard from these producers was a desire to celebrate the territory as singular and independent from the other Sangiovese-focused areas of Italy. In that regard, they are largely succeeding. Chianti Classico has come a long way since I started drinking wine seriously 20 years ago.

It is also important to note that many of these wineries are making surprisingly epic sparkling wine (especially Poggerino and Fèlsina), quenching rosé (seek out Istine and Tenuta Lilliano), fabulous red wines from international grapes (e.g. Ricasoli’s Casalferro Merlot), and of course, world-beating olive oil (beeline to Badia a Coltibuono and Fèlsina for that).

My point: the Chianti hills between Florence and Siena should never be seen as monolithic.

But Chianti Classico, that moving target of a wine, occupied most of my thoughts. What do all these recent changes mean for me and my readers? And have they gone far enough? Undoubtedly, they are steps in the right direction, but I think some confusion will persist. As much as Burgundy holds a certain ideal over the wine world, the unique complications to understanding Chianti Classico are still more Bordeaux-like in nature, just based on how the land is parceled, the tradition of blending, and the unique nomenclature used for products.

Ideally, I’d love to see the area do the following:

Eliminate the Use of International Varieties in the Blend

The time has come to ask, what do they really add? To me, they add a dose of sameness. Their use is an alignment with Napa and Bordeaux, and while the practice may have garnered the world’s attention decades ago, it no longer should be mixed up with the “Chianti Classico” name. The O in DOCG stands for “origine,” and if producers are serious about showcasing the origin of their wines, than these international varieties need to be shed from the disciplinare .

When blended with Sangiovese, even in small amounts, Bordeaux varieties quickly strip away the elements that make Sangiovese so unique. It starts with the disappearance of the grape’s savory, meaty flavors, and then quickly shifts towards a substitution of its citric-like acidity in favor of plusher textures. The Chianti hills can make exquisite Merlot, but those wines can always be labeled as Toscana IGT.

One observation on this topic (incidentally, outside of the Chianti Classico zone) has been seared into my memory. At Selvapiana in the Chianti DOCG subzone of Rufina — and a specialist in the wines of the Bordeaux-centric Pomino DOC — I asked winemaker Federico Giuntini “at what percent do international varieties start to dominate Sangiovese and make the wine more about that international taste? Ten percent?”

His answer: “That’s already too much.”

That’s all it takes. Throughout Italy, wines made up of 85% to 90% of a single grape are often allowed to be labeled as varietal, but in the case of Sangiovese meeting up with Merlot or Cabernet, 90% may as well be a minority.

Open Village Labeling to All Categories

As places like Istine and Rodáno proved (as well as Cigliano di Sopra), the entry-level annata wines of Chianti Classico can be some of the best indicators of village identity. In Burgundy, if you want to understand the broad strokes of Morey-Saint-Denis, you don’t start with the Grand Cru Clos de la Roche. That will only tell you about the specific grandeur of that one site. You must start with a village wine.

So why not do the same in Chianti Classico?

At first blush, this might seem contrary to the producer’s desired outcome of scaling wine categories and charging a premium for the more terroir-centric wines, but it is actually not mutually exclusive. Which leads us to this next item.

Refine the Focus of Riserva and Gran Selezione

The difference in aging requirements between these two categories (24 versus 30 months total) is just shy of negligible. Their primary difference lies in the Gran Selezione’s recent ban on international varieties and its mandate of a minimum 90% Sangiovese. After that, it’s purely philosophical.

Some wine lovers have the opinion that the Gran Selezione category is an excuse to use more oak and charge more money, and unfortunately, some producers have given them ammunition in this argument. Other producers are finding ways to bolster the category’s intended stature.

I am not of the cynical opinion that Gran Selezione is a meaningless category. For one, oakiness has nothing to do with its guidelines: that’s a producer’s decision. Secondly, what I learned is that both categories can provide exceptional wines worthy of long cellar aging. I’ll say it again: both categories. Not once did the Riserva wines seem like “a middle child” in the product mix. (Also: annata wines can be absolutely delicious, and more appropriate for more occasions at the table. Does that mean they are of lesser quality? Certainly not).

Because of this, I think the notion of a “quality pyramid” should be set aside. What consumers want to know is whether the wine is a blend or varietal, and whether it is a single-vineyard or not.

The simplest fix for that is to have the same aging requirements for Riserva and Gran Selezione (24 months? 30 months? I honestly don’t have a preference). They ought to have the same blending formula guidelines as well (90% Sangiovese minimum).

With that playing field leveled, the Riserva wines ought to be confined to the best selections from multiple vineyards, blended together. Prototypical examples would be Badia a Coltibuono’s Riserva and Istine’s “Levigne.”

Then the Gran Selezione category ought to be confined to single-vineyard wines. This ultimately will mean that most Gran Selezione wines will be varietal, but occasional blends of native grapes could show up in the mix. Prototypical examples would be Ricasoli’s “Colledila” and Villa Calcinaia’s “Vigna Bastignano.” This change would also mean that many of today’s top Riserva wines would shift over to Gran Selezione without sacrificing what makes them special, such as Rodàno’s “Vigna Viacosta” and Poggerino’s masterful “Bugialla,” which I think is the best wine in the whole zone. There would also be a few Gran Selezione — notably, Ricasoli’s “Castello di Brolio” — that would shift back over to Riserva due to their multi-plot approach.

So then how would consumers know if their Gran Selezione (or Riserva) is a blend of native grapes or not?

Add One Last Bit of Nomenclature

Varietal Terroir Fever comes at a cost. The art of blending is underappreciated in today’s wine world, and I think Chianti Classico needs to own its tradition of blending by allowing producers who still blend different grapes to call out such a practice on the label. Yes, that label is getting wordy (clearly, I have no problem with wordiness), but if my first suggestion of eliminating international varieties were adopted, it would clear the way to celebrate the alchemy of Sangiovese and Tuscany’s other native red grapes.

That term could be something as simple as assemblaggio tradizionale (traditional blend). It could appear on any wine at any category level, and while it may add yet another layer of knowledge for us to memorize, I think it would also pique the curiosity of many wine drinkers.

The Thing About Oak

Lastly, we come to oak. Yes, let’s talk about it. After all, overuse of new oak remains the biggest obstacle to identifying Chianti Classico in the glass. That’s because new oak in barrique and tonneaux barrels routinely interferes with the purity of flavors presented by the grapes involved. The practice often renders the wines anonymous.

But this problem isn’t exclusive to Chianti Classico. It’s an issue everywhere. While market forces and modern taste have swung the pendulum toward fewer oaky imprints and more of the inherent wildness found in Italy’s native grapes, I still frequently encounter Italian red wines smudged with the vanilla bean and cola flavors of oak.

The purist in me would love to suggest a draconian ban on new oak, or even — a step further — formal guidance on which oak is most appropriate for Sangiovese. But that hasn’t happened anywhere, nor would it ever be adopted. And frankly, nor should it be. You can only legislate quality so much. Forcing such a sweeping change to the “hardware” at each winery — we’re talking hundreds, sometimes thousands of barrels at certain wineries — would be a burdensome financial cost on each winery and would require sacrifices elsewhere in the production of their wines. It is not a fight worth having.

In the end, if we are serious about buying, serving and certainly cellaring Chianti Classico — or any Italian red wine for that matter — we all need to read up on who is who and what their philosophy with oak is.

Tasting Reports on Chianti Classico

So which Chianti Classico wines should you buy, drink now and cellar? Subscribers of Opening a Bottle have access to my three new Tasting Reports.

- Tasting Report: Chianti Classico Annata

- Tasting Report: Chianti Classico Riserva

- Tasting Report: Chianti Classico Gran Selezione

For just $79/year, you can get access to all wine reviews plus join us for any of our regular online classes. Subscribe to Opening a Bottle today.

Note: My travels through the Chianti Classico region were greatly supported logistically and financially by the Consorzio Vino Chianti Classico, who transported me to each winery and covered accommodation costs. Without that support, the trip would have never happened. However, the wineries were selected by me out of editorial consideration, and no compensation was involved for any of this work. Opinions are exclusively my own. Learn more about our editorial policy.