The trajectory of Schiava in Alto Adige is a familiar one in the world of Italian wine. It goes like this: a grape variety has an inconspicuous history. It quietly spreads across a specific area and for centuries it yields a lot of simple wine. With the advent of the international wine trade, the grape becomes maligned for its plainness. The grape is even uprooted in favor of something more popular … And then, one day, a few winemakers give it the attention and care it deserves and allora! Suddenly that grape is an important icon for the winemakers of its home territory.

Such is the current renaissance of Schiava, a grape that grows throughout southern Germany but is most closely associated with (and celebrated in) Italy’s Alto Adige, where it seems to be eclipsing its indigenous counterpart, Lagrein, in stature.

For purposes of this First Taste Guide, we’ll focus entirely on its expressions from Alto Adige where it is known — as everything is in the region — by two names: the Italian Schiava and the Tirolean Vernatsch. (Note: in Germany its called Trollinger).

For a deeper perspective, I also called Advanced Sommelier Chelsea Carrier, the Beverage Director for Cushman Concepts in New York, where she oversees the wine programs at o ya, Covina and the Roof at the Park South Hotel.

Carrier loves Italy’s wines, and in particularly, is an advocate for some of the nation’s less obvious ones. She’s bullish on Italian white wine, proclaiming they can go toe-to-toe with most luxury white wines in the world. And — as I found out when we met in Alto Adige at their annual Wine Summit — she is also quite curious about Schiava’s potential.

At the summit, we were given a day in the vines with winemakers. While I attended the Pinot Nero boot camp, Carrier joined the field-study session devoted to Schiava.

Now, I know how I like to serve Schiava at home (hot summer days when I want red!), but I don’t have to sell it to anyone. And Schiava can still be a tough sell. Carrier’s first-hand experience recommending Schiava to guests — combined with what she learned in the vineyards in September — gave me a whole different perspective on Alto Adige’s resurgent red.

So hop aboard the Schiava train. Let’s take a first taste.

3 Reasons to Try Alto Adige Schiava

- Why So Serious? – Contemplative, serious red wines hog all the attention. For once, let’s shine a light on something with a lighter tone and open a Schiava.

- You Have Developed a Taste for Gamay – No, Schiava is not related to Gamay (nor is Alto Adige similar to Beaujolais in any way) but the tones, body and acidity of this wine remind some of Brouilly or Régnié.

- You’re Looking for a Versatile, Reliable Sipper – With its light body, bursting aromatics and crisp acidity that screams “chill me,” Schiava is a superb wine to open on a porch in summer … or, ditch the chill and open it as a warm-up act to your Christmas roast. It goes both ways.

About Schiava and Its Appellations

The term Schiava refers to a group of related grapes that are often co-planted and blended together: Schiava Grossa, Schiava Grigia, Schiava Gentile and Schiava Nera. The origin of its name may refer to the vines being “enslaved” by being tied to poles, rather than growing wild across the ground and into the trees. Schiava (the term) was used by the ancient Romans for a handful of different grape varieties, but it was the Middle Ages that this particular family of grapes was first documented as such in Alto Adige.

“Schiava was known for being, well, kind of a ‘garbage’ grape,” says Carrier, referring to its recent history. Despite its ancient roots in Alto Adige, Schiava became the beating heart of bulk production throughout the 20th century, with really only two markets in mind: local consumption and German grocery stores. “But it’s such a tasty little grape varietal and to do it traditionally and be producing such great quality as they are in Alto Adige right now … It was rather eye-opening for me.”

Schiava remains the most widely planted grape variety in Alto Adige (14% of total plantings as of 2017), but not by much. In fact, there is a good chance that Pinot Grigio will overtake total plantings in the near future due to its commercial success. (And yes, some people think Pinot Grigio is a “garbage grape,” too, but Alto Adige proves that notion wrong in spades).

Appellations

Schiava and its white wine brethren do not compete for the same acreage. It prefers the lower slopes of the Adige River Valley, while the white varieties thrive at higher elevation.

Schiava has two strongholds in Alto Adige: the vineyards around Lago di Caldero south of Bolzano, and the solar-shield hillside above the city known as Santa Maddalena/St. Magdalener. The Lago di Caldero/Kalterersee DOC overlaps into Trentino and is entirely devoted to Schiava. Wines must include at least 85% of the grape, and specially designated vineyards close to the lake (which benefit from its climate-moderating forces) can append “classico” to the label.

Santa Maddalena/St. Magdalener is treated as a subzone within the broader Alto Adige/Südtirol DOC, where it is common to add up to 5% Lagrein to the final wine. This landscape can be best seen from the Renon Cable Car as it rises out of Bolzano. The rolling green carpet of Schiava vines with the Dolomites in the distance is among the prettiest vineyard landscapes in the world.

Viticulture

But even in the ideal growing conditions of Lago di Caldero and Santa Maddalena, Schiava requires a dedicated focus and special attention to yield a compelling wine.

“Schiava is a fickle little grape,” Carrier says. “It is prone to mildew and pests because of its thin skin.” That thin skin, combined with large berries, creates a wine of delicate juiciness with little tannin. Young-vine Schiava reliably yields a juicy, uncomplicated, thirst-quenching wine. It is only when the vines reach a robust age (such as 50-plus years) that they start to reveal depth and complexity.

Carrier noted that the best Schiava vines are still trained the old-fashioned way, on an overhead pergola system. “I was surprised by this. Most people associate pergolas with bulk-production, but multiple producers said ‘it’s the only way to grow this grape.'”

During her time in the vineyards, Carrier tried Schiava grapes from both the Guyot and pergola vines, and noted that the ones from the Guyot vine-training system, which are more exposed to the sun, were “tannic and almost abbrasive.” Meanwhile, those from the pergola vines had a more delicate and refreshing taste.

Another benefit of the pergola vines? Protection from hailstorms, which can decimate a year’s crop in the blink of an eye.

Production

“Some of the wine we tasted in the walk-around tasting were hammered by oak,” notes Carrier. “And that can take away from the beautiful florality and tart fruit character of Schiava.”

Because of this, oak aging needs to be subtle, which is why many winemakers ferment the wine in stainless steel or concrete tanks, then move it to large, well-used oak casks — which impart less oaky character to the final wine — for maturation.

It is interesting to note how Schiava compares to Lagrein (Alto Adige’s other local red) in terms of its ability to age in bottle. One Santa Maddalena winemaker told me (off the record) that he feels Lagrein’s window for optimal drinking is much shorter than Schiava. One of the wines featured below proved this point at its five-year mark.

Your First Taste of Schiava

The first time I encountered Schiava was indelible. It was early in my “wine-drinking career,” and the notion that wines could share aromatic compounds with other elements of nature was still a bit of a mystery to me. But there it was, in my glass: almonds. Almond extract, to be more specific. Every time I return to Schiava, that note — sometimes faint, sometimes potent — is there. As are strawberries or red currants, honeysuckle, as well as autumn leaves and sometimes tilled soil. What Schiava does not taste like is cotton candy, as some suggest. (Aromas can be personal, but that seems pretty far out there as an over-arching generalization).

“The drinker that would drink Schiava would probably be in that Gamay or Beaujolais camp,” notes Carrier. She likes to recommend Schiava wines to dining guests who are seeking something light and refreshing — a sort of white-wine drinker’s red. Though, she says, the scenario where Schiava best enhances a guest experience is when they want to go straight into Barolo or Brunello with their appetizers. “I often have to decant those wines. So while they wait for them to open up, Schiava is a great way to get the meal started.”

And for food pairings, Carrier recommends game and richer styles of fish. Plus, she adds “it could even be an outside-the-box Thanksgiving wine.”

Who’s Who in Schiava?

Which ladders up to which producers handle Schiava the best. It is important to note that the vineyards of Alto Adige are mostly small plots tended by families, which leads to a lot of co-operative wineries. Most of these are of exceedingly high quality, and the mentions below are by no means exhaustive.

From Carrier’s standpoint, she loves the tradition-minded winery of Manincor near Lago di Caldaro, as well as a small producer in neighboring Trentino — Castel Noarna.

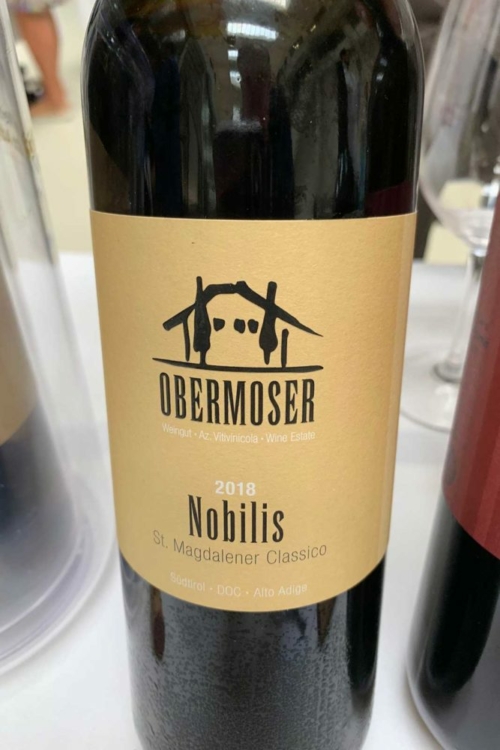

My introduction to Schiava was through Abbazia di Novacella, but I have since come to appreciate their Santa Maddalena (★★★★ 1/2) a little more. In fact, I prefer Santa Maddalena wines over varietal Schiava and those from Lago di Caldero ever so slightly. The splash of Lagrein seems to add a greater depth and fruitiness that nicely rounds out the tart elements of varietal Schiava. Of these, the Santa Maddalena/St. Magdalener from Obermoser called “Nobilis” (★★★★ 1/2) is the most intense and vibrant that I’ve tried, with a surprising plushness. Another abbey — Muri-Gries — produces a very fine Santa Maddalena (★★★★ 1/2) which is strongly suggestive of mint and dried cherries.

Also look for the varietal Schiava from St. Paul’s Kellerei (★★★★ 1/2) which is pitch-perfect and has a long finish. On the nose, its suggestions of dried strawberries, autumn leaves, earth and roasted almonds are quintessentially Schiava.

Finally, look for the Cantina Cortaccia Schiava Grigia (★★★★ 1/2), which is a rare monovarietal version of Schiava. We recently opened this wine alongside a Dolcetto d’Alba for Thanksgiving (upon Carrier’s suggestion), and its a very compelling match. At that table, the wine is upright and distinctive enough to be noticed over the din of tart cranberry sauce and gravy-slathered turkey, yet modest enough to not take over. It’s profile is classic Schiava, but I wouldn’t say I notice much difference in taste between this Schiava Grigia and the traditionally blended Schiavas of the area. However, at five years of age, it underscores the point I heard in Alto Adige: Schiava may be light and fruity, but it has better aging potential than many think.

Note: Wines for this article were provided as samples by Wines of Alto Adige USA upon a story-pitch request from the editor. Wines of Alto Adige also covered for my accommodations, meals and programming during the Wines of Alto Adige Summit in September. Learn more about my editorial and travel policy.