Traditional Winemaking

A team of men at Donnafugata destems the Zibbibo grapes after they have completed the drying process. ©Kevin Day/Opening a Bottle

A team of men at Donnafugata destems the Zibbibo grapes after they have completed the drying process. ©Kevin Day/Opening a BottleThis icon pertains only to activities inside the winery, not the vineyard. But even then, the terminology can get murky. That's because traditional winemaking means many different things in many different contexts. In essence, when a wine or winemaker is marked with our icon of a large botti cask (above), it means that they employ one or more traditional techniques in the winery that are pivotal to the outcome of their wine.

The spectrum of techniques is wide, but the commonality is the same: preserving tradition not for tradition's sake, but for its inherent wisdom.

Opening a Bottle Asks ...

One of Italy's most traditional wines is Tuscany's vin santo. In this video, winemaker Federico Giuntini shows us the special casks used in its production, and explains the process by which it is made.

Why Traditional Winemaking Matters

A funny thing happens when humans do an activity for millennia: they stockpile expertise and pass it down to the next generation. Such is the multi-faceted history of wine, whose current iteration would merely be the outermost ring of a giant Sequoia tree. That ring, however, has seen more alterations and improvements than any other. What we have come to recognize as wine is often the product of technologically advanced, mass-produced techniques employed in hyper-hygienic conditions in a modern winery. And because of it, wine has never been better.

But our ancestors didn't get us here by making unpalatable swill. True, they may have had a hard time avoiding stuck fermentations and exploding bottles. Oxidation alone took centuries to solve. However, in their cleverness came a certain kind of preservation. As the wine world hit its stride in the later half of the 20th century, so too did sameness. "Modern" winemaking had leveled the field so much, that — in order to reclaim distinction — producers looked backwards. Or, in many cases, producers who never surrendered tradition suddenly seemed fresh and ultra relevant.

I may mark a wine or winery as "traditional" for a variety of reasons, be it troglodyte facilities for aging wine, the use of controlled oxidation under flor as seen in Sherry and Vin Jaune, the "farmer fizz" of bottle fermentation seen in pét-nat and col fondo wines, and even the spectrum of appassimento wines made from the drying of grapes to concentrate sugars and tannins.

Traditional winemaking's persistence manifests in many different forms, and is highly dependent on local custom, especially as it pertains to the vessels used for fermentation and aging. For instance, the use of clay qvevri vessels for fermentation may be traditional in the Republic of Georgia, but its use in Friuli-Venezia Giulia and many other places is still a bit of a novelty. (You will note that clay fermentation vessels have their own icon in this publication).

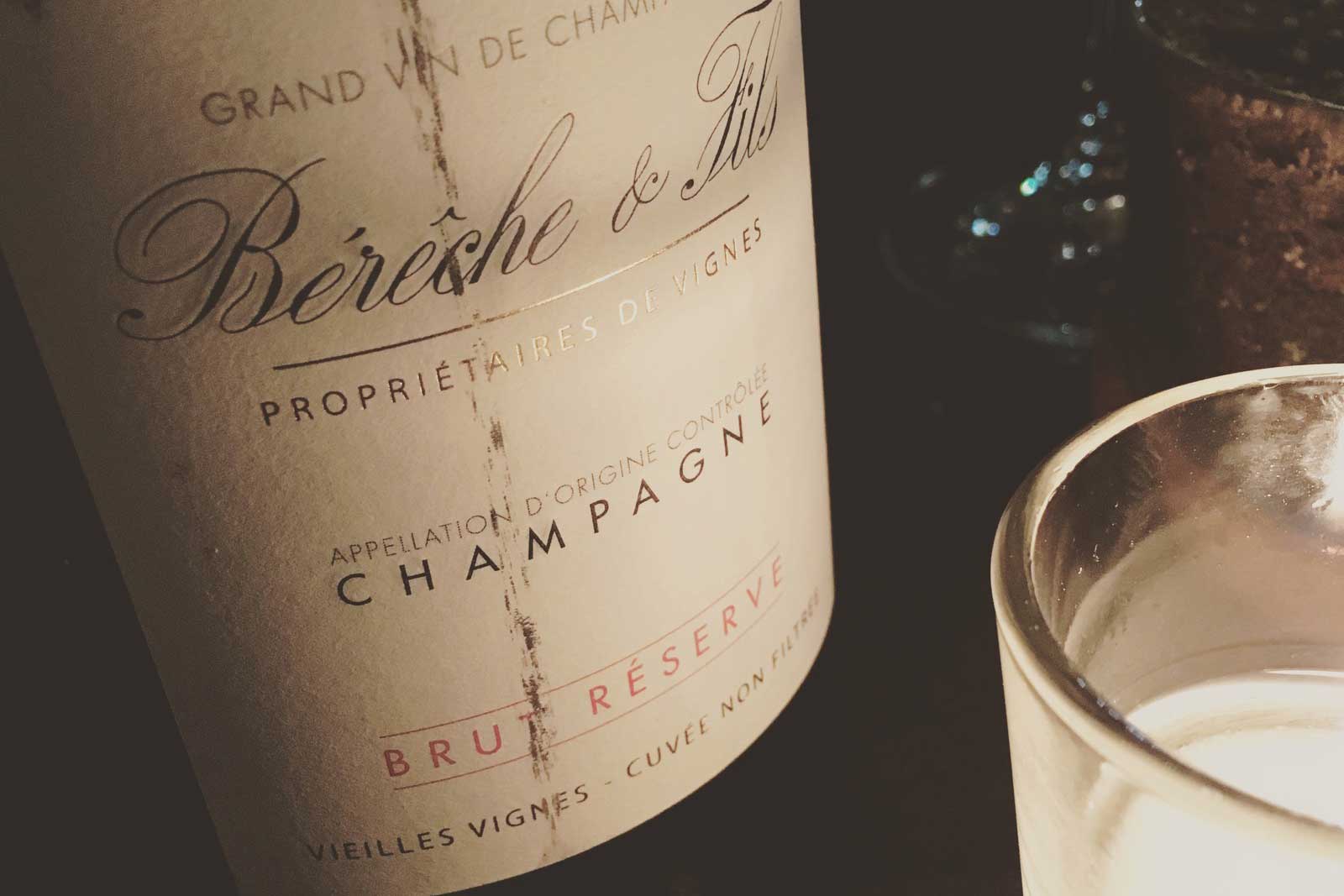

Perhaps the biggest delineation between what is modern and what is traditional — at least for purposes of this Nebbiolo-obsessed magazine — lies in Barolo and Barbaresco, where the size of the oak vessel used plus the length of maceration time leads to spirited debate (larger botti casks and longer maceration times being "traditional," smaller barriques and short maceration being "modern"). This divide was often likened to a war in the 1980s and 1990s, and it has certainly cooled with the latest generation, but even then, you'll find steadfast adherents to tradition such as Bartolo Mascarello, Brezza and Oddero, whose wines have a beautiful elegance and earthy character that is only revealed because of their careful, traditional choices in the winery. In fact, the botti vs. barrique debate permeates much of Italy's red wines, showing up very visibly in the wines of Tuscany, Sicily, Lombardy and Abruzzo.

So do traditional winemakers make better wine? That is for you to decide for yourself. But I will say this: their wines are more reliably distinctive, exciting and certainly compelling from a storyteller's standpoint. Don't be surprised if you see that botti icon showing up on many of the pages of Opening a Bottle.