For the last 50 years, few Americans have been more synonymous with the independent, family-owned, terroir-centric wines of France and Italy than Kermit Lynch.

Born into a family of teetotalers in the San Joaquin Valley, Lynch found his way to Berkeley, California in 1972, where he established a wine shop and importing business that redefined how many American’s would come to appreciate wine. The business was revolutionary for its embrace of traditionally made wines that held terroir as the highest of virtues, and it was pivotal in showcasing the depth and diversity of France, in particular.

“Only in this century have we seen the hard-earned knowledge of the ancients discarded, almost overnight, in the name of progress.”

Kermit Lynch

Adventures on the Wine Route

Today, everyone in the wine business talks up terroir, but in the 1970s, ’80s and even ’90s, Kermit Lynch’s focus defied the times. With the much-hyped vintage of 1982 — and the rise of Robert Parker and his contemporary wine critics — an age of bombastic wines came to the fore. Lynch, however, was unswayed. He saw wisdom in those making wines that were honest and aligned with the rhythms of nature, not bent by the conveniences or guarantees of technology.

As he wrote in his brilliant 1988 memoir, Adventures on the Wine Route, Lynch mused on the “ancient French vigneron,” and the “colossal oeuvre” they created: “The taste of the grapes told them when to harvest. The taste of the wine told them when to bottle … Do not think for a moment that they were ignorant people who did not know better … Only in this century have we seen the hard-earned knowledge of the ancients discarded, almost overnight, in the name of progress.”

If all of this sounds familiar, it is likely because you’ve walked into a natural wine bar or had a sommelier espouse the value of natural wine to you tableside. Lynch’s push to import and sell wines of individuality and authenticity may have been weirdly ahead of its time, but it was undoubtedly a precursor to today’s natural-wine movement, which prizes uniqueness and a connection to nature’s gifts from the vineyard over everything else. But as I found out when I was afforded the chance to interview him in June, Kermit Lynch feels that there are also a lot of things that the “true believers” of natural wine get wrong.

Our Conversation

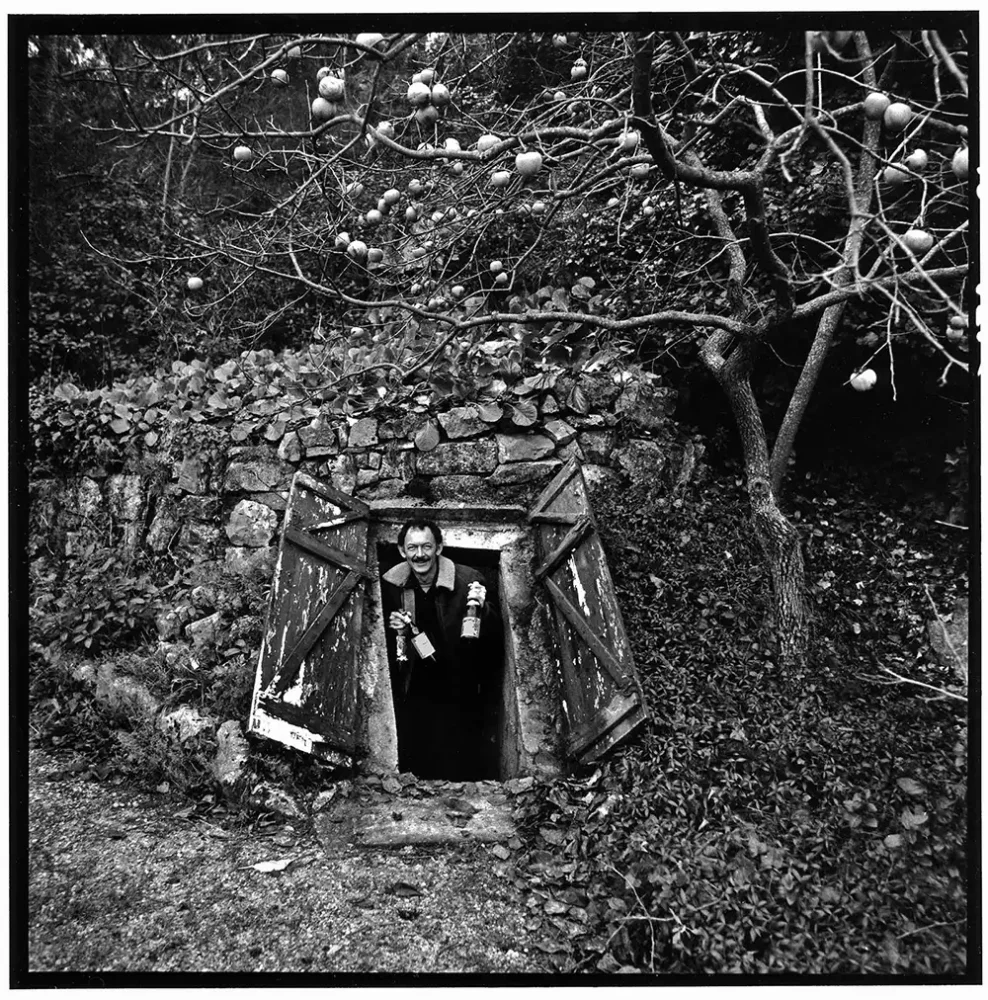

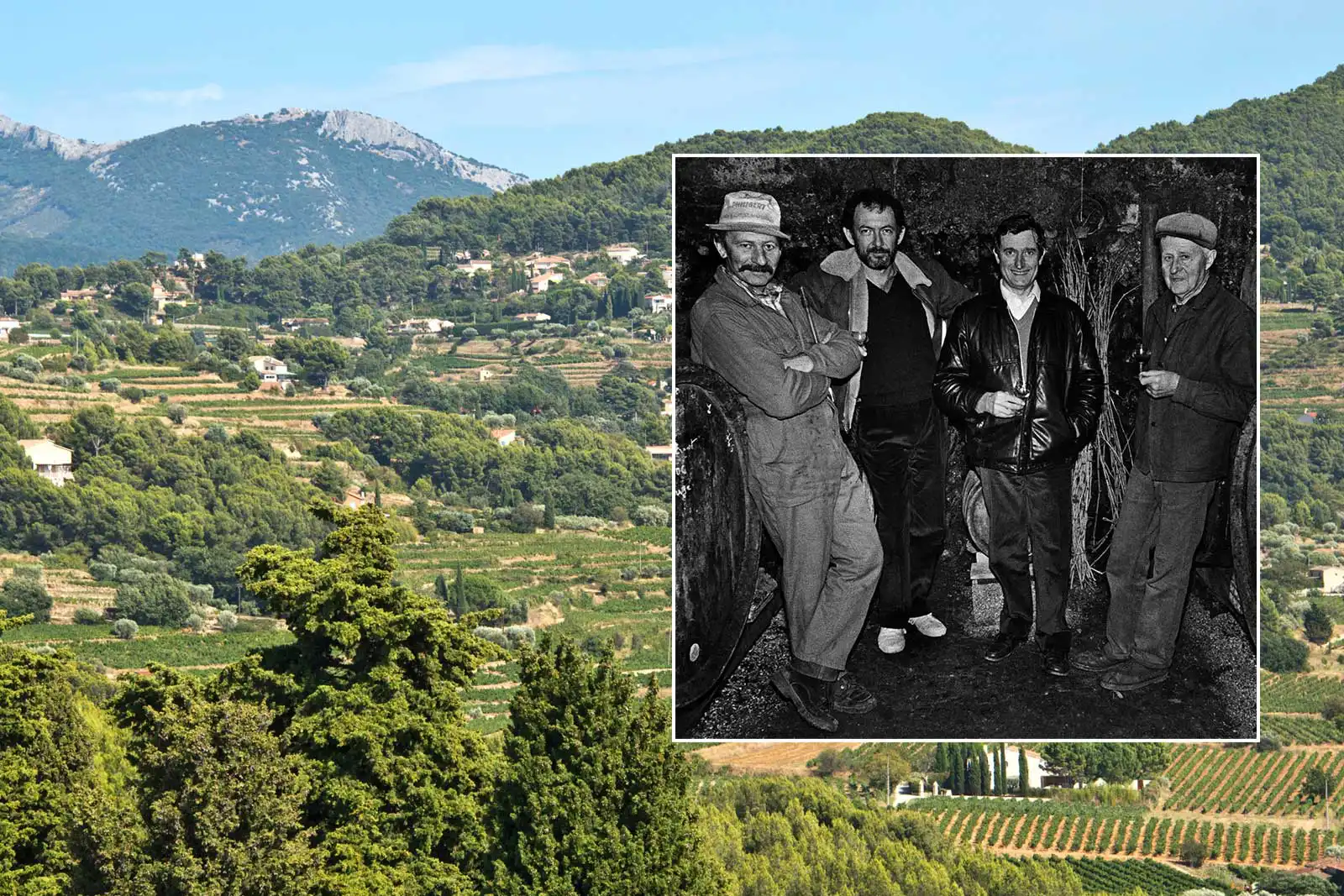

Lynch is now “very retired,” as he put it, spending much of his time at home in the South of France near Bandol. He recently became a grandfather, and his long-time associate, Dixon Brooke, now runs the company with his son, Anthony, firmly involved in the day-to-day operations.

I have been wanting to speak with Kermit Lynch for a long time. If there is another book that captures the soul of European wine better than Adventures on the Wine Route, I have yet to read it. Lynch’s sense of humor, his intelligence and his fiery opinions create a tapestry on the page that is impossible to turn away from, even 34 years after it was first published. It gets better with a second read.

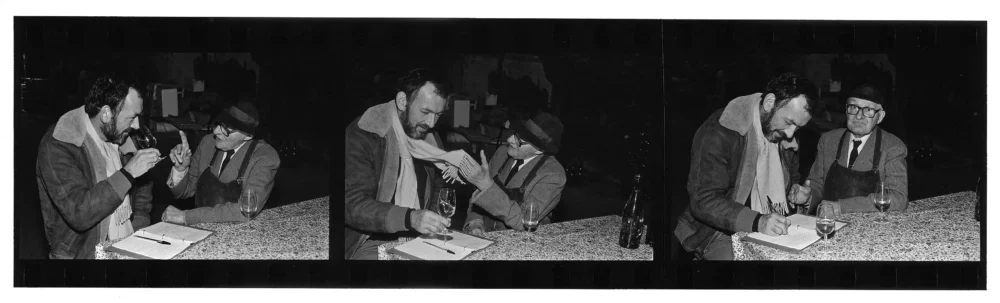

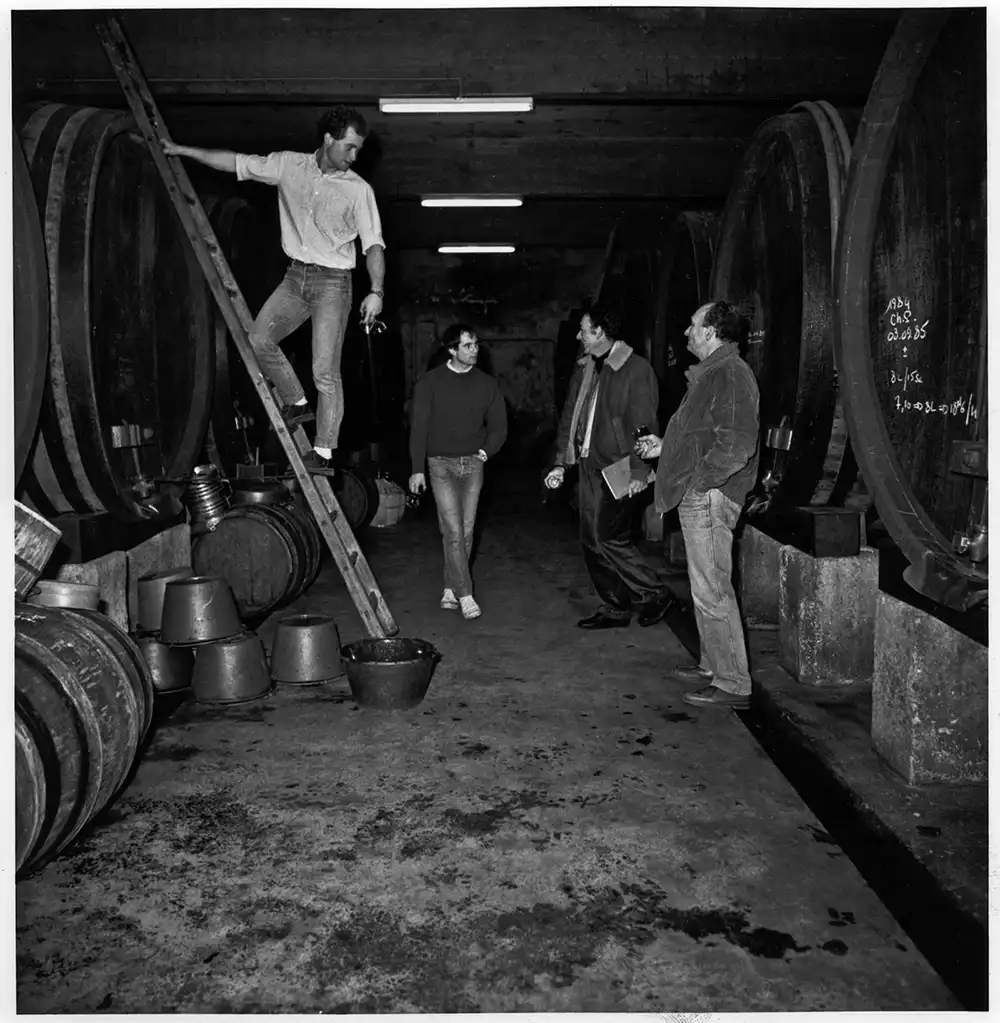

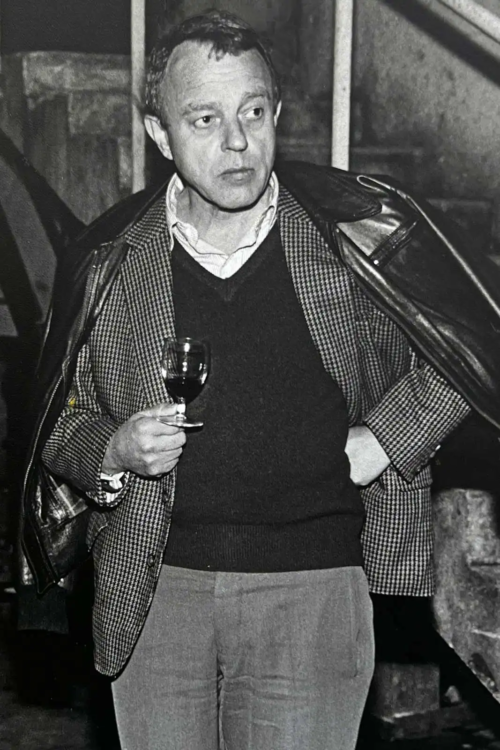

Lynch speaks in much the same way as he writes: methodically, patiently, but with a glint in his eye that suggests he knows it is just wine, and that we cannot take ourselves too seriously. There may have been a certain gravity to the topics we covered, but there was still always room for a laugh here and there, which I’ve tried to convey in the transcript below. As a photographer myself, it is also a privilege to be granted permission to publish many of the images below by Lynch’s wife, renowned photographer Gail Skoff.

On Finding a Life in Wine

Kevin Day: Let’s go back to the beginning for a moment: did you find wine or did wine find you?

Kermit Lynch: I learned just three or four years ago, that it is a question of DNA. Isn’t that amazing? I was visited by a fellow from Ireland. He was writing a series of books about the so-called “noble families of Ireland” and the Lynches are one of them. There was a Castle Lynch — I think there still is, but it has become a pub or something [laughs]. He interviewed me for his book and sent me a copy of it, and there is a whole series on these Irish families. And I started reading the book, and I read that in the 15th century there was a Lynch who was an importer in Ireland — a wine importer! It hit me! Like somebody punched me in the chest, I just thought, “oh god,” I thought I’d just left everything in my family behind, because on the Lynch side they were almost all teetotalers, fundamentalist preachers, you know? I was off in Berkeley amongst the infidels, drinking. [Laughing]

The book went into how the Lynches were in the wine business in the 15th century, and it turns out I am from the same branch of the Lynches as the guy who went into Bordeaux and married a woman with a wine château and turned it into Lynch-Bages.

Kevin Day: Wow. So there is a connection between that Pauillac estate and your family?

Kermit Lynch: Well, yeah, that goes way back. I actually visited once and said “I’m Mr. Lynch and I am here to claim my inheritance—”

Kevin Day: [Laughing]

Kermit Lynch: Thanks for laughing, because they didn’t laugh. So there was that.

Other things that I had forgotten that came back to me because of that [story]. I was born in the San Joaquin Valley, surrounded by grape vines, olive trees, fig trees … And my father — who was a teetotaler — he worked two years for the Roma Winery in the San Joaquin Valley. And an uncle of mine worked for another winery near Delano, and was their winemaker until he fell and broke his back and couldn’t continue. So I had forgotten all about that, it was from when I was really a baby. I have some memories of my uncle’s place out in the middle of the vines with a windmill and some horses that were just surrounded by grapes. But it kind of struck me how the Lynch family — and even my own family in California — was involved in the wine business. When I got into the business myself I had no idea. I didn’t know any of that.

For myself, I was living in San Luis Obispo from when I was 9 years old. When I was a senior in high school, a pair of Berkeley graduates — a young married couple — moved into the house next to me and my parents. And they drank wine with meals, and they started inviting me over for lunch or dinner sometimes, and they always had wine on the table. This was when I was 16. They drank wine with meals! I got into that. When I moved out to college, I started buying wine to drink with meals. And so that’s how I got started.

Kevin Day: It seems there’s always been a culinary connection with you and wine, from your book to your newsletters and the recipes you include …

Kermit Lynch: Well, it was never on the table at my own home. My mother, for example, her idea of cooking was taking a TV dinner out of the fridge and putting it in the oven. It was, I guess, when I first went to Europe — I was 28 years old — and that’s where I really got interested in food and wine in a serious way.

“It kind of struck me how the Lynch family — and even my own family in California — was involved in the wine business. When I got into the business myself I had no idea. I didn’t know any of that.”

Kermit Lynch

On Wine Criticism and Wine Media

Kevin Day: I have to ask you about wine criticism and wine influencers, because there were two passages in your book — Adventures on the Wine Route — that stood out to me as they relate to the wine industry in 2022.

For instance, you wrote in the introduction “Wine is, above all, pleasure. Those who make it ponderous make it dull. People talk about the mystery of wine, yet most don’t want anything to do with mystery. They want it all there, in one sniff, one taste.” There are several other passages snuck in there as well, among them “vintage charts are the worst kind of generalization. Great wine is a contradiction of generalization.” This was all written in 1988.

I am wondering if you feel like the wine media landscape of today — inclusive of critics and writers but also influencers — is any closer to getting it right, or are we further than before?

Kermit Lynch: Further than before. I can’t read wine tasting notes any more from the critics. It is just laughably dishonest. Most people don’t have a chance to do it, but critics do have the chance to visit wineries, to talk to the winemakers, to taste the wine in the barrel, then taste it later when it comes out in bottle. These tasting notes where the wine writer finds 10 different aromas, you know, “inside of the cocoa bean from the Maldive Islands.” One, how many people have smelled what these guys are talking about, you know? I haven’t!

“Wine is, above all, pleasure. Those who make it ponderous make it dull. People talk about the mystery of wine, yet most don’t want anything to do with mystery. They want it all there, in one sniff, one taste.”

Kermit Lynch

Adventures Along the Wine Route

I have a wine cellar and I’ve tasted these wines from the time they were made in barrel, then bottle, and now in my cellar for 10, 20, 30 years sometimes. When you go to taste a certain wine one day, you can say “oh my god, the raspberry aroma just leaps out of the glass.” You go back three months later and you might say “oh my god, now it’s black cherry.” Wines evolve. If they’re alive, they evolve. But finding all of those aromas all the time with every damn wine?

I love in Eric Asimov’s book, there is chapter where he talks about that. He went out and bought a bottle of wine — I think it was a Malbec from Argentina. And he found three reviews of it. The verbiage for each wine in their paragraph review, well, there was not one word in common! … To me, that’s not wine: searching for all of these bizarre aromas. You’d tell someone to go buy the wine because, “you really like raspberries?”

Kevin Day: So what ought to replace that? Because people still want to know, “if I’m gonna buy this wine, what is it going to taste like?”

Kermit Lynch: I think the first thing is, is it a sound wine? Is it balanced? Is it correct, in terms of not being oxidized or too oaky? Once you arrive at the point where you can tell people “this wine is well-made and has no flaws,” you should let them know how it should be used. Because, like I said in that book, if you drink Château Margaux with an artichoke, it’s terrible. Taste a nice rosé with an artichoke and it can be fine.

So that’s important. If you say “this is a great wine,” I’ll respond “great for what?” And that’s the job of a critic.

I’m having trouble these days finding red wines light enough to enjoy in the summer. All the wines are blockbusters these days, and it’s a combo of critics who only liked big wines but it is also global warming now. I think instead of leading the client to find some exotic perfume in the wine, it is better to say “this is a wine you can enjoy on a hot August night with a grilled fish,” or something.

On Venturing Into Italy

Kevin Day: Adventures on the Wine Route focuses solely on France, but I am also curious about your early exploits in Italian wine. What year did you venture into Italy to expand your business and how much of a cultural transition was that for you?

Kermit Lynch: It was very early in my career. I’d say my first buying trip was January or February of 1974. And I took two buying trips that year. Then it got to be 2, 3 or 4 per year.

What happened was that there was a crisis in the wine business. That’s really why I opened my own store. Nobody would hire me. It was a huge recession, like we haven’t seen since. Nobody could sell their wines. I bought Château Grillet for $1 bottle, for example.

Frank Schoonmaker had a huge inventory to sell — a catalog as thick as a New York phone book. And all his stock was in France and Germany … Well, I had been to Europe and traveled with Schoonmaker’s head guy, Karl Petrowsky. Right off the bat, I was tasting from some of the best estates in Germany, Austria, Italy, France and Spain. And I learned a lot from those tastings, because when I started I had been buying a lot of wine from a guy who imported négociant wines. And Frank Schoonmaker’s wines were almost all domaine-bottled. So I could compare and see that the négociant wasn’t exactly on the up and up, and I could see how the different personalities and different wine families were. That culture attracted me.

So Italy was part of that trip. I think the first trip to Italy I went with a California winemaker, Joseph Swan, one of the best winemakers I met in my career. But what amazed me about it: one, the wines, unlike today, were much cheaper than French wines. But I think we were also struck by how much better the wines were than we were led to believe, at least given what we were tasting in the United States. And also, I must say, the food we were eating at the wineries and restaurants, we were bowled over by it. I couldn’t wait to get back to Italy. And in fact, that is when I decided to narrow down. At the beginning, I was only importing about 10% Italian wine, but I didn’t want to give up because I didn’t want to give up traveling … or the dining [laughs].

On Appellations of Origin

Kevin Day: Are there too many appellations of origin in France and Italy? Put another way, do you think that there are some areas that have been awarded the status that have never really demonstrated “somewhereness,” to use Matt Kramer’s word?

Kermit Lynch: That’s never occurred to me. I’m not sure how I feel about it. I do have a lot of feelings about the appellations and I’ve changed my mind a lot about it over the years, having experienced it firsthand.

At the beginning, I thought it was an incredibly good idea to try and preserve these historic wines and wine areas and their character. But I kept seeing in France how it became a system of bureaucrats who really didn’t know wine.

There is some saying, that “France gave up its king and now it has millions of bureaucrats.” [Laughs]. But there are rules that were meant to be followed that, over time, haven’t worked out. The people who formed the rules made mistakes, including people I value a lot. The French put these things in place, and now it is a Bible: “if it ain’t in the Bible, you can’t do it!”

I ran into that here where I live [near Bandol]. It was a vineyard in the old days. When I moved in, I planted grapes and I wanted some Marsanne because I like those Northern Rhônes so much. And I found out I couldn’t plant it because it is not on the list of allowable grapes. I said “I don’t care. I’m just going to bottle it as my house wine. I mean, my God, I will only have enough for about one barrel!”

“No, no. You can’t plant it. This is the Bandol appellation, you cannot plant it.”

Kevin Day: It sounds a bit like trying to take a banana into Hawaii.

Kermit Lynch: Well, you know, interestingly enough, in Bandol, the Vermentino or Rolle [as it is called in France] is not allowed. That’s the Mediterranean white grape! It is the white Mourvedre [laughing] and they don’t allow it.

But also, listen to this: they allow Sauvignon Blanc, which for one thing ripens a month before the other grapes. So they put a lid on creativity and evolution and on developing better wines by using a better grape variety for certain terroirs. That really amazed me.

One of the guys who influenced me so much was Lucien Peyraud at Domaine Tempier, and he had a lot to do with the INAO for Bandol. In fact, he and the Baron Leroy — who was a very important guy in creating the appellations, he had Château Fortia in Châteauneuf-du-Pape — the two of them were assigned, or rather assigned themselves, to go to Corsica and define the appellations for Corsican wine. This was around the 1960s. They recognized only about 4 or 5 Corsican varieties, when there are many others. There are a lot of old Corsican grape varieties, but those were not recognized. But they introduced Syrah, Grenache, Carignan, Bandol and Rhône varieties [laughing]. It is colonialism! “The natives don’t know what they’re doing here.” That really took [away] a lot of my enthusiasm for that [the way appellations are handled].

The INAO is so slow to move, to allow any change … it is almost like winemakers are prohibited from finding the right grapes to cope with climate change. Look how dangerous that is.

On Climate Change

Kevin Day: In the 1980s, you noted that industrialization was threatening the traditional wines you loved — an abundance of filtration use, technology dependency, basically that post-war mentality holding on. Are you now seeing a similar trend, albeit, perhaps one beyond a vignerons’ control, with climate change rendering a lot of the wines and wine regions you loved unrecognizable?

Kermit Lynch: Absolutely. It was sort of a double whammy.

When I got into it, if Bordeaux wines were at 11 degrees [alcohol] naturally, the winemakers were happy! … When you tasted young Bordeaux at the time, those wines had very vegetal aromas. We called them “green.” I’ll bring up Parker again, because he could not stand that vegetal quality. In fact, he refused to review Loire reds because they have so much of a vegetal quality. So there were all those years where people wanted higher and higher alcohol and bigger and bigger wines.

“One was a mode in the French sense, a fad: ‘a blockbuster is better than a light, pretty wine.’ And then boom: global warming comes along.”

Kermit Lynch

And then once Parker’s influence went down, we have global warming, which is taking it to yet another step. One was a mode in the French sense, a fad: “a blockbuster is better than a light, pretty wine.” And then boom: global warming comes along.

A lot of winemakers act like today is the end of global warming. No, we have to cope with tomorrow. Global warming, it ain’t over! So this preserving the appellations and not allowing people to try new grape varieties … it is just self-destructive.

Kevin Day: Well, you do have Bordeaux allowing Touriga Nacional among a few other new grapes. That could affect the flavor of what Bordeaux will taste like for future generations …

Kermit Lynch: Sure.

Kevin Day: Is that something that, in the interest of survival, we are just going to have to tolerate? That what you were tasting in the 1970s is a bygone era?

Kermit Lynch: It was already a bygone era with the Parker period. Every vintage was suppose to taste like 1982. Back in the 1970s it was so easy to tell which was Margaux, which was Latour and Haut-Brion. Today, it is just not the same.

On Natural Wine

Kevin Day: Given how the wine world has embraced traditionally made, minimal intervention wines over the last 10 to 15 years, do you feel a sense of vindication, or is it more complex than that?

Kermit Lynch: Of course, I take pleasure from it. Sometimes I am surprised that — because I kind of broke the ground for that — that I am not listened to in terms of what my experience has taught me.

“There is a puritanical streak in natural wines that just leaves me out. It is no longer important if the wine is correct or not. In fact, there is really a belief that a flaw is a sign of a natural wine. That drives me up the wall.”

Kermit Lynch

There is a puritanical streak in natural wines that just leaves me out. It is no longer important if the wine is correct or not. In fact, there is really a belief that a flaw is a sign of a natural wine. That drives me up the wall.

I will use just one example, but it is very telling I think. A lot of the people who are in this natural wine movement are against any sulfur. Ok. I’ve done tastings with winemakers where we do different cuvées of exactly the same wine with varying amounts of sulfur to see what that does. And you get to find out: when can you smell sulfur? And it is quite low.

And then we found out that it doesn’t take much sulfur to protect the wine. It really just takes a teensy bit. In Alsace, for example — my God — they used to use 200ppm! You only need about 15ppm. So it is very little bit, but it will keep your wine from fermenting in the bottle. And fermentation smells bad! [laughs]. I received a case of wine here this year where every bottle in it was fermenting. You pull the cork and it goes pop, just like champagne. Shake it and it fizzes out, and it was supposed to be a still wine but they didn’t add any sulfur.

A lot of people [today], they don’t do that kind of studying. They just get it in their mind: “natural wine.”

To me the question is, what is this true believer thing? “If it is not zero [sulfur], then it deserves to be jailed!” [Laughs]. You find out that sulfur, thank goodness for it. Those great Château d’Yquems wouldn’t have existed, those great old Bordeaux wines, the Romanée-Contis, none of them would exist in the form they are as an old bottle if they hadn’t had a little sulfur. It is not a religious thing we are talking about, it is making wine! [Laughing]

Everyone has a different palate. Some people can smell really well, other people they like different things. My palate, in my opinion, I would taste wines in France or in California at the winery, in the barrel. Then, when it was for sale, I’d taste it again, and almost always it had lost something. I’d wonder, how did it lose all that? It was me trying to get the same thrill from the bottle that I got from tasting in the cellars. That’s where the filtration and adding too much SO2 at bottling got to me, how it would diminish the quality of the wine. That’s where using reefers came in, to try and make the wine taste in California like it did in France.

So that was my goal and I worked on it with a lot of wineries.

On The Future of His Family Business

Kevin Day: Your son, Anthony, is now an integral part of Kermit Lynch Wine Merchant, and one cannot help but make the connection that the wineries you have represented — more often than not — are a multi-generational family affair as well. How did Anthony come into the business and was maintaining a familial link to the business important for you, or was it a completely different thing for you when he joined?

Kermit Lynch: It was completely different. I never talked to him about joining the company. I never saw that as a goal … He was a psychology major at the university, but every summer that he was in school I put him to work. The first year, he worked in the office in Beaune. That meant he met a whole lot of winemakers, and did a lot of tastings. And the next year, I put him in Berkeley. I can’t remember if I put him in the office or in the warehouse, but it was like that: I was moving him around so he would get to know more of the business. And now my son-in-law is working for the company — he has been for about a year — and I am doing the same with him. He was working for a financial institution in Manhattan and moved out to California with my daughter … We call him PJ, but his name is Paul Blandori, and my daughter is Marley. And I am just about a two-week-old grandfather for the first time.

Kevin Day: Congratulations. That’s a big shift I am sure.

Kermit Lynch [smiling]: It feels pretty good!

Kevin Day: Whether you intended it or not, are you now starting to see shades of what it’s like to have a family business that perhaps you saw in the wineries you represented all those years?

Kermit Lynch: No, no. I wasn’t influenced by that. But when my son told me that he wanted to come work for the company, it was funny how good it made me feel, because like I said, I wasn’t trying to maneuver him into that at all. And I surprised myself by having a very positive emotional reaction to it. And the same with PJ. It’s probably natural.

And also I do remember telling Anthony and Marley, that when they were choosing a career, it is hard to find a métier that is more fun than the wine business. And that’s important when you decide what kind of work you’re going to do … [Here he started laughing, as if realizing how this sounded]

Kevin Day: So you did plant a seed?

Kermit Lynch [laughing]: Well, yeah, that work can be fun, and how important that is in one’s life. It is more important than one’s salary, for example.

Winemakers & Wines We Love from the Kermit Lynch Portfolio

Essential Winemakers of France

- Charles Joguet (Chinon)

- Château Thivin (Beaujolais)

- Maestracci (Corsica)

Essential Winemakers of Italy

- Punta Crena (Liguria)

- Sesti (Brunello di Montalcino)

- La Marca di San Michele (Verdicchio dei Castelli di Jesi)

And 10 Great Wines

- Albert Boxler Crémant d’Alsace Extra Brut (Alsace )

- Domaine Ostertag “Les Jardins” Pinot Gris Alsace (Alsace )

- Tenuta Anfosso “Antea” Vino Bianco (Liguria )

- Maxime Magnon “La Bégou” Corbières Blanc (Languedoc-Roussillon )

- Guy Breton Régnié (Beaujolais )

- Charles Joguet “Clos de la Dioterie” Chinon (Loire )

- Regis Bouvier “En la Rue de Vergy” Morey-Saint-Denis (Burgundy )

- Giovanni Montisci “Barrosu” Cannonau di Sardegna (Sardinia )

- Domaine Les Pallières “Racines” Gigondas (Southern Rhône )

- Guido Porro “Vigna Santa Caterina” Barolo (Piedmont )

Featured image photo credits: Both black and white images ©Gail Skoff. Image of Bandol vineyards at Domaine Tempier ©Kermit Lynch Wine Merchant.

Note: This article was updated to include new wines and optimized images in August 2023.

Finally got around to this- a wonderful read here. This will likely change the way I describe wines. There’s so much to agree with Kermit Lynch about, especially thoughts on sulfur. I was in a seminar with Alpana Singh recently, who aptly said about sulfites, “they’re like deodorant- you may THINK you don’t need it, but you really do.” Last week my husband and I shared a cheese board at a wine bar that specializes in low intervention wines. They had un-sulfured apricots which were brown and tasteless. It seems people are getting desensitized to faulty wines and faulty fruit! Anyway, thank you for your content. Your opinions are completely trustworthy to me.

Thank you for your note and kind words. Isn’t that interesting about the apricots. Yet completely believable, too! Yes, people can take things to extremes without thinking.